History and WEB in Spain

Updates

2012 (tv) | 2014 (web) | 2016 (web) | 2016 (tv) | 2017 | 2018

by María Antonia Paz and Julio Montero

-

Introduction and state of the question

As we stated in the conclusion to our first paper, this second stage will involve analysis of the information that popularisation of history websites contain about certain subjects. We chose to study the first page of Google results in each case. We also wanted to look into the possible differences that the various different language versions of one single informational tool – namely Wikipedia – offered on the same subjects.

The initial proposal focused on Google searches relating to Spanish subjects and events. We have changed the criteria and carried out searches in Spanish on topics which are more closely linked to Europe, and to the European Union in particular. However, the analysis protocol remains as originally proposed. The subjects we carried out searches on include: a historical process (history of the European Union); the biography of a figure who is linked to events and processes which involve several European countries (Willy Brandt), tracking a celebration which involves several European countries (commemoration of Europe day) and a specific event which, despite having taken place in Germany, is also associated with Europe as a whole: the fall of the Berlin Wall. Lastly, we analysed the differences in information provided by each language version of Wikipedia on the subject of the languages of the European Union.

In making our decision to analyse only those results offered on the first page of a Google search, we took into account the fact that 90% of people who search for information on a particular subject stick to one of the addresses from that selection. The criteria the search engine uses to make this classification[1] are largely based on the amount of links to the page from other sites. Google also takes “hypertext matching” into account, i.e. the number of times that the search term (or terms) appear on the corresponding webpage. As a secondary consideration, it looks at the sources cited and its position and hierarchy. These details are of interest since they determine the actual contents of the results pages. To put it another way, the editors of these webpages strive to have their content appear elsewhere and will use key terms repeatedly throughout the text, focusing more on them than on explanation or historical development (which would involve references to other processes and terms and a consequent loss of visibility).

We realise that by choosing to consult only those websites offered on the first page of results, we are limiting ourselves not just to the most frequently consulted pages, but also to the perspectives and versions of the subject which have been read by the majority of the people who made the same searches. This implies that we are dealing with the most popular information, which would probably be of least interest to a historian seeking information for their research. We are aware of the limitations this implies for our analysis: we are only looking at the information obtained by non-specialists who are interested in an issue (probably driven by little more than momentary curiosity). This limitation becomes an advantage if we consider that what we are looking at is the most widely disseminated information on the net about this particular issue.

-

Material and methods

The first Google search of the study (conducted on August 31, 2012) was for “History of the European Union[2]”. The second was for the biography of “Willy Brandt” (September 4, 2012). The third was for “Commemorations: Europe Day” (September 5, 2012). The fourth search, for “The fall of the Berlin Wall,” was carried out on September 6, 2012. As we have mentioned, we analyse each one of the websites that appear on the first page of a Google search. Finally, Wikipedia searches for the term “European Union” in Castilian, Catalan, Galician, Basque, English, French and German were carried out on September 5, 2012.

Our analysis focused on the following points (detailed in Appendix I): type of page (official, unofficial, private), level of information, material offered and links provided (to check which subjects and materials the search terms is related to and assess the importance of the page[3]). We have also covered the number of visits and the presence of advertising (which helps to assess the page’s impact), among other aspects. Next, we studied the elements which define interactivity (characteristics of Web 2.0): user comments, accessibility, and most importantly, content, level of understanding and value of the materials offered. Finally, it is also of interest to know whether these pages simply present the facts or also provide explanations and interpretations. We believe that this set of indicators will help to assess not just the information itself but also the way in which it is provided, as well as the potential influence it may have.

In short, we intend to analyse some specific cases which offer clues for later research. We do not wish to account for the potential role of the internet in the historian’s work in general, but rather the potential of some of the options arising from analysis of information about areas of recent European history, with specific reference to the process of creating the European Union.

-

Analysis and results

3.1. The model web page

When you conduct a Google search for “History of the European Union,” what appears at the top of the first page of results is an advertisement. This could be considered to interfere with the historian’s work, but we must take into account the fact that we are working with a search tool – Google – which in addition to whatever aims we might think it has, there is another very obvious one: to generate profit. Advertising is one of way of achieving that aim, and is of interest to us because we cannot rule out the possibility that additional means of generating income might influence the information Google supplies. In this case, the ad is for a company that offers online and classroom-based online courses on subjects such as the external relations of the EU and legal and administrative systems of the EU, among others.

Of the other nine entries on the list, two are videos which have been uploaded to YouTube and seven are web pages. Sites belonging to non-official organisations predominate (see Table 1). The order in which pages appear is significant, because third and fourth place on the list are taken up by websites aimed at students (the third place one is aimed at teachers as well). In its online incarnation, the press is represented by two newspapers (El País and El diario montañés) as a key source of information on the net, proving that its influence still lives on in the new era. The two YouTube videos confirm that the audiovisual medium has a pre-eminent place in today’s society.

Table 1. The first nine pages found via a Google search for “History of the European Union”.

| Name of the page | Type of organisation responsible |

| 1. Europa.eu | Official organisation |

| 2. Wikipedia | Unofficial organisation |

| 3. HistoriassigloXX.org | Official organisation (CNICE) |

| 4. El Rincón del Vago | Unofficial organisation |

| 5. Enciclopedia Libre Universal en Español | Unofficial organisation |

| 6. El País | Unofficial organisation |

| 7. Cápsulas históricas. YouTube | Official organisation (Univ. Católica de Santiago de Guayaquil, Ecuador) |

| 8. Vídeo Historia de la UE. YouTube | Private individual (Israel González) |

| 9. El Diario montañés | Unofficial organisation |

The majority of these are aimed at the public in general. However, el Rincón del Vago (the page’s name, which translates as ‘Idler’s corner’, is not coincidental) and CNICE’s page (part of the Spanish Ministry of Education), are targeted to students between 16 and 17 years old, who are studying Primero de Bachillerato. The official EU page has a special section for children (Kid’s zone) and teachers.

Only La Enciclopedia libre and the YouTube videos display the number of views. The former states it has had 66,614 views, despite its poor content. Cápsulas Históricas attracted 16,297 and the second video (put together very simply by editing photos and text with music), gained 5,850. It is amazing to think that this content about the history of the European Union has reached such a high number of people.

Five of the sites offer links to other pages, usually within their own site (as is the case for European Union, Wikipedia, Enciclopedia libre, El Rincón del Vago) allowing the reader to expand content on proper names, countries, institutions and treaties. Only Wikipedia directs users to the European Union’s official page, and only HistoriassigloXX.org provides links to materials which supplement its own information, which generally lead to newspaper articles (El País). In Wikipedia and the Enciclopedia libre the user can edit the text to broaden its scope or make changes, which makes these collaborative pieces of work.

There is advertising on both of the newspaper sites (though it is more extensive on the El País site than the El diario montañés site). El Rincón del Vago also carries advertising, which confirms that the site is regularly visited; and the video made by a private individual carries advertising for Banco Santander. Israel González’s video is flagged as a “video highlight”: a label which is difficult to understand once you have watched it. In general, the advertising is not aggressive. It is usually placed to one side of the text and does not interrupt or hinder the reader.

Apart from Wikipedia, none of the others offer a bibliography, but then users are not looking for one. They are normally trying to clear up a particular doubt, and links are more practical for that purpose as they do not “interrupt” the process of documentation. This concept of ease is confirmed by the scarcity of forums – a tool typical of the new technologies which allows user interaction. Photographs are the most frequently used primary source. The official website of the European Union is the only one which features videos of politicians from different stages of the integration process. However, the videos are slow to load and are seen in a stuttering form. In short, the popularisation of history on the web disposes of the classic options for expansion – such as bibliography- yet nor does it make use of the tools which are inherent in the new technologies (multimedia, interactivity).

In the example analysed, the predominant model is of a web page which is promoted by an unofficial organisation, aimed at a non-specialist audience, and which has achieved a high number of views. The only means of expanding the information is through the links offered. The pages are not multimedia: they combine text with a few photographs. They do not carry advertising. In terms of content, facts predominate, in the form of chronologies and lists (of institutions for example), rather than explanations. The simple, brief and clear option is chosen rather than the elaborate account.

3.2. What they tell us: historical accounts on the web

There is little difference between the information on these websites and traditional historical accounts. Interactive resources are rare. Only the official website of the European Union stands out in this regard. For example, it offers an interactive visit to the living room of a home which allows the user to discover how daily life has changed since the country entered the European Union. When we click on the different objects (such as a purse), a dialogue box appears, telling us that “in the wake of monetary chaos, the EU approved the single currency…” If we click on the magazines, it tells us about gender equality policies, etc.

Another interactive element commonly found on other pages is the opportunity to rate the information. This is normally limited to clicking on ‘Like’[4]. Of our sample, comments are only enabled on the YouTube videos. On Cápsulas Históricas, there is one comment which has been marked as spam, and makes the following disturbing observation: “The European Union is Hitler’s dream come true”. More comments have been posted on the second video, suggesting improvements to it: “Lolita’s song (Moi…lolita, by Alizee) is too much”; or “Good video. Just one thing. The Euro came into circulation in January 2002, not 2001”. The author says thanks for the help and promises to make another video incorporating the suggestions. Other comments are so poorly phrased or spelt as to be incomprehensible.

All of the pages are highly accessible [5], except the official site of the European Union. History is to be found in the section entitled “How the EU works” along with Basic information, Countries, Facts and figures, Institutions and bodies and Work for the EU. One would not normally relate ‘History’ with ‘How something works’.

The pages which offer the most complete general information are the official EU site, Wikipedia and Historiassiglo20. The one which provides the most specialised content with regard to Spain is El diario montañés, since the information was compiled specially for the occasion of Spain’s presidency of the European Union.

The official EU site has two main sections, one covering the founding fathers of the institution, and another which covers the stages of integration. These stages are divided into decades, with two levels of information given about each: an at-a-glance summary of the basics, and the option to obtain further information. According to the page itself, the most visited links are: 10 historic steps, key dates in the history of European integration, and EU symbols. This shows that the user prefers specific topics which highlight the most important things for him/her (just ten historic steps are enough) and that a timeline is sufficient to give us an idea of the whole process. The EU website is perfectly suited to these demands: there are no “explanations” [6] nor does it contextualise the facts. There are no criticisms, no negative aspects, no insurmountable problems. In fact, the last stage, which covers the present day, is entitled “A decade of opportunities and challenges”.

Wikipedia is also largely descriptive, but unlike the official website, it highlights decisive moments in the history of the European Union such as the budgetary crisis of 1999. It takes the form of an article, divided into sections. It offers more detail than the EU site, but the way it is written is often confusing, being neither clear nor precise. The only specific reference to Spain is a photo of Javier Solana, who was High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy at the time.

Historiassiglo20 developed a teaching unit for the bachillerato[7] modern history class. It has not been updated: its coverage ends in 2001 and does not explain the institutions of the European Union. The biographies of leading personalities are very brief, but include a few sentences or brief extracts of speeches. Unlike the previous pages, it does explain the European Constitution. Historiassiglo20’s page comments on the most relevant facts and situates them chronologically. It pays particular attention to the concept of European citizenship established in the Maastricht Treaty, appreciating the rights and opportunities it confers, while critical of its inadequacies. It includes a glossary, texts and activities designed for pupils, in Castilian, English and Portuguese.

The two sites which offer the most inadequate information are El Rincón del Vago and La Enciclopedia Libre Universal en Español. The first is very limited. It settles the entire formation process of the European Union in a single paragraph. It lists the institutions, but does not explain them. Also, there is a list of admissions by year up until 2004. The photos do not have captions: it is not easy to identify events or protagonists.

The case of La Enciclopedia Libre Universal is more striking. It too is very schematic and does not mention any of the failed attempts at European integration. Its visual presentation is very poor: it only contains two maps with the admissions, the flag and some tables with accession dates. This page also takes the form of an article. The last two sections (“Future expansion” and “Other possible expansions”) are based on the author’s own speculation.

The account in El País is also very limited: it consists of a chronology which goes backwards from 2003 (when it was written), to the antecedents, without any supporting material. Meanwhile, the report prepared by El diario montañés is more detailed. The story is presented in various tabs: The European Union, Spain in the EU, the fight against the crisis, a unique voice in the world, Europe for its citizens, the Lisbon Treaty, and a multimedia section where six current affairs videos are offered. The report reproduces the ‘ten historic steps’ content without mentioning that it comes from the official EU site. It contains no information about the politicians who led the process.

Of the two videos, the one produced by the Catholic University of Santiago de Guayaquil is the best. It uses archive images (the capture of Berlin by the allies, images of prisoners in concentration camps), photographs of the different stages of integration, and animated maps with flags. The editing is done well, there is a connection between the image and the voiceover, and we hear the anthem of the EU as a musical backdrop. Its contents explain the historic steps, though in this case just the first five. The video ends with the creation of the Euro in 1993 and its coming into force in 2002. The other video (by Israel González) is a simple Power Point presentation which alternates between text and photos, and contains some errors[8]. The music is out of place.

3.2.1. Different versions.

Our analysis of the differing interpretations has focused on how they report on the origins of the European Union. Two of them (El Rincón del Vago and the video by Israel González) do not mention the origins at all, and El País barely does so, stating simply that: “The postwar period in Europe brought currents of unity to the countries of the old continent”. At the opposite end of the spectrum is Wikipedia: it lists the empires established by force (the Roman Empire, Frankish Empire, Holy Roman Empire, First French Empire, Nazi Germany) and the dynastic unions as antecedents.

Of the rest, five pages trace the origins of the EU back to the Second World War. Avoiding another similar experience would seem to be the initial objective of European integration (according to the official website, Cápsulas Históricas and Wikipedia). El Diario montañés talks about the need to create a supportive and peaceful Europe (using current terminology and references) and Wikipedia notes that the European economy was in ruins and that the United States and the Soviet Union had greater economic and military power, implying that Europe wanted to regain power to match up to them. The Enciclopedia Libre Universal states that “the Cold War was the origin of political and economic union”, while Wikipedia claims that “the Cold War put the brakes on the initiatives for a United Europe”. The clearest, most complete and well-ordered explanation is offered by the secondary-school teaching unit.

The question arising from this is how does the user react when faced with these contradictory pieces of information? We do not know if the user consults several versions before choosing one, but if so, what criteria lead him to pick that particular option? It would be interesting to know if there are any criteria available on the net as regards selecting an account from the many offered by this type of basic search, and if so, whether these criteria differ and in regard to which variables.

In short, the webpages analysed offer not just a great deal of facts and chronologies, but also different interpretations. This diversity –and contradiction in several cases- is not backed up by primary and/or secondary sources. There do not appear to be any established codes on quotation (or plagiarism) and there is a possibility that any of them may lose their place on the first page of Google results after a few days.

3.3. Variations in the biographies

A search for “Biography of Willy Brandt” brings up two of the same websites as the previous search: Wikipedia and HistoriassigloXX. We could say that they are common references for this type of history-based Google search conducted from Spain. Four pages specialising in biographies of famous people (see Table 2) also appear on the list. Other results include the websites of a little-known online newspaper (La Insignia), a foundation created by an Argentine social-democratic politician, and the tourist office for Brandt’s birthplace (Lübeck).

Table 2. Results of a Google search for “Biography of Willy Brandt”

| Name of the page | Type of organisation behind the page |

| Biografíasyvida | Unofficial organisation |

| Wikipedia | Unofficial organisation |

| Buscabiografias.com | Unofficial organisation |

| HistoriassigloXX.org | Official organisation. CNICE |

| Wikiquote | Unofficial organisation |

| Lainsignia.org | Unofficial organisation |

| Fundación Estevez Boero | Unofficial organisation |

| Biografías.es | Unofficial organisation |

| Busca-biografias.com | Unofficial organisation |

| Lübeck-turismo.de | Official organisation (Lübeck town hall) |

In this list there is just one page specifically aimed at students (HistoriassigloXX.org). The number of links is significantly lower than in the first search, which is understandable since the search term “Biography of Willy Brandt” is of a more specific nature. Wikipedia and Wikiquote offer links to pages within their own site and to external ones, while Biografías only offers internal links. There are no stats on the number of visitors, except on Biografíasyvida, which specifies that ‘Like’ [Me gusta] has been clicked on 429,678 times. Willy Brandt’s entry is not one of the most frequently visited. The most in-demand biographies on Biografíasyvida were in fact:

- Fernando Alonso

- Aristotle

- Eminem

- Albert Einstein

- Galileo Galilei

- Paris Hilton

- Napoleon

- Britney Spears

The range of eras, professions and importance of the personalities whose biographies are being searched for gives us an idea of the varied interests of internet users: in terms of demand, Fernando Alonso and Aristotle are on a par.

Apart from Wikipedia, none of them provide any bibliography or videos. The only visual accompaniments are photographs, but only half of the websites (five) use them. The most commonly repeated photo (which will become the image that users form of Willy Brandt, Photo 1), is a headshot taken in a studio. It shows a mature, smiling, affable man: there is no symbol or context to link him with a particular party or ideology.

Photo 1. The most commonly used photo of Willy Brandt

Five sites carry advertising (Biografíasyvida, Buscabiografías, Biografías.es, Busca-biografías.com and LübeckTurismo). The variety of products and services advertised (low cost airlines, fashion, language courses for companies, travel search engines, etc.) do not point to any particular user audience.

In summary, a very similar webpage model to the previous one but with this case greater specialisation in this case (pages devoted to biographies), although this does not mean that the information provided is of greater quality. It is a little more detailed (rather than just simple timelines), but it is still very basic.

3.4.Peculiarities of the biographies: content analysis

These web pages lack interactive elements. In contrast, on Wikipedia –where interactivity is part of the project’s general approach- users can rate the article in terms of how trustworthy, objective, complete and well-written it is. The ratings for the article on Willy Brandt are quite high, although very few people (three) have actually rated it. The article scores between three and four points out of a possible five. Accessibility is good. It offers the best information (the most detailed and complete). It is structured in chronological sections which span from Brandt’s early years and his experience in the Second World War, up to his political career before, during and after his time as Chancellor. It even covers his family life (marriages, children), his death and the memorials to him. The text is illustrated with eight photographs.

The other pages are a distillation of that information. His escape from the Nazis in 1933 and his stay in Norway stand out due to their somewhat epic tone. There is a list of the positions he held, his defence of human rights, his role as a driving force in the process of European unity, and in the reduction of tensions with the Soviet Bloc. The discourse by Estévez, the Argentine politician, is the most moving. It draws a more human picture of the man. La Insignia includes an address entitled ‘Democracy, liberty and socialism’. We do not know if it is by Willy Brandt himself or a member of the social-democrats. The address is written in the first person and sets out a broad political manifesto.

3.4.1. Not all of the sites agree

In order to assess the level of the content we have chosen to focus on one particular aspect of Brandt’s life story: his participation in the Spanish Civil War. Most of the pages consulted deal with this subject in a certain amount of detail.

Four websites link Brandt to the Civil War. Biografíasyvida states that he fought on the Republican side. Wikipedia restricts his connection to a visit to Spain. According to the politician Estévez, Brandt took part as a journalist. Biografías.es is not very clear: “He becomes part of the German Socialist Workers’ Party, SAPD, which allied itself to the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) in Spain during the Spanish Civil War in which he represented the party”[9]. As we can see, the most consulted biography sites do not coincide on features of a certain importance, which suggests limited critical thinking was involved in drafting them. It seems that instead, a simple task of selecting and merging pieces of information together from an initial text, in this case Wikipedia, was carried out.

3.5. Commemorations: Europe Day

Among the first results offered for the commemorations there are many which refer to official pages: those of the European Union, the Spanish government (Ministry of Education), a regional government (Junta de Andalucía) and a trade union (UGT). There are also more pages targeted to teachers than in the previous cases (Table 3). There is an obvious interest in promoting this celebration and reaching younger children (pre-school and primary education) in particular. The presence of newspaper sites (La Razón and Ideal) on the list confirm this.

Table 3. Results of a Google search for “Europe Day”

| Name of the website | Type of organisation | Audience it is aimed at |

| Wikipedia | Unofficial organisation | General public |

| European Union | Official body | General public |

| European Commission. Spanish Representation | Official body | General public |

| Google Images | Unofficial organisation | General public |

| La vuelta a Europa con Wali | Official body (Government of Andalucía) | Teachers |

| Ite.educación | Official body (Spanish Ministry of Education) | Teachers |

| Ideal.es | Unofficial organisation | General public |

| aulaintercultural | Official body (UGT, FETE Educación) | Teachers |

| Larazón | Unofficial organisation | General public |

| Scouts.es | Unofficial organisation | Young members |

| Profes.es | Unofficial organisation | Teachers |

Source: Compiled by the authors

Google Images provides the broadest range of visual material – more than two million results including posters, photographs of countries, maps…. This figure is obviously beyond any comprehensive enquiry. No videos on the subject were found on the first page of Google results.

The desire to provide material for the classroom means there is an ample supply of links (both external and internal); the number is markedly higher than the links for historical processes (History of the European Union) and biographies (Willy Brandt). However, the medium -internet- continues to impose its own means of providing information: there is hardly any bibliography (again, just Wikipedia) and no opportunity to take part in a forum. Nor is there any information on the number of visitors to each website. Since they belong to institutions, the majority of the pages do not carry advertising. The only ones to feature adverts are the two newspapers. Four pages feature photographs which give an account of the celebrations in different countries and show promotional posters of Europe Day in previous years. One of the sites (Ite.educación) includes an extract from the Schuman Declaration, which is considered the origin for the creation of the European Union. Therefore, the main characteristics of the web page model we have seen for the previous searches are largely maintained.

3.6. What readers are told about Europe Day

These websites do not feature any multimedia or interactive elements. The teaching activities proposed for use in the classroom are traditional and unidirectional (draw a drawing, colour in the flags, a crossword puzzle, fill in a questionnaire, word games etc). We have not been able to evaluate user perception because, although the option of leaving a comment is provided on almost all of the sites, this opportunity is never taken up. The exception, once more, is the Wikipedia article: it scores 3.5 out of 5 in the rankings given by around 20 people.

In this case there are no great differences in the contents offered by each website. They all explain, briefly, the origins of the celebration (the Schuman Declaration), what it represents (it is a symbol of the EU, along with the flag, the anthem and the single currency) and the events which are usually arranged. Only Wikipedia points out that “in practice none of the member countries of the Union organises high level festivities like those that take place for the national celebrations of each state.” The rest mention the celebrations without going into any assessment.

The most critical site is Profes.es, which points out the historic difficulties in the formation of the EU (“there were many meetings and disagreements between the different European countries, although little by little, the members of the Union have managed to form a sturdy organisation…”) as well as the current problems related to nationalism (“However, many still consider the process of integration in this supranational organisation to be an attack on their identity as a people”).

The newspapers depict the current situation: Ideal explains how Europe Day was celebrated on Twitter, and reproduces a series of tweets. La Razón briefly summarises the programme of events organised in different cities (talks, informative workshops, conferences, children’s activities and the distribution of educational material). Finally, the ASDE-Scout España page highlights the values defended by the European Union and takes advantage of the commemorations to encourage its members to take part in activities on a European level with the aim of making contact with scouts from across Europe.

3.7. Investigating a particular event: “The fall of the wall”

The first Google results page features 11 websites. Two of them do not fit our purpose – one of them belongs to a foundation which raises funds for the fight against cancer (Fundación Fuseon). The other is a YouTube video which has been blocked by EMI because of its content. Wikipedia is first on the list once more. Among the media websites there are three newspapers: Libertad digital, El Mundo and La Información as well as a programme made by Televisión Española (Informe semanal). Three of the pages are aimed at students (see Table 4), while the rest are targeted to the general public.

In comparison with the previous searches and results we must highlight the use of audiovisual material to illustrate the information. It seems that the more recent the subject is, the more audiovisual material is available on the net. This would seem logical since there are more documents, which are of better quality and easier to access.

Table 4. Search results for the term “The fall of the wall” listed on the first page of Google.

| Name of the website | Primary sources provided | Audience the site is designed for |

| Wikipedia | Photos | General public |

| Redescolar | 1 Photo, map | Students |

| Imágenes | Photographs, maps, newspapers | General public |

| Lainformación/especiales | Video | General public |

| El Historiador.com | — | Students |

| Monografías.com | — | Students |

| Informe semanal | Video | General public |

| YouTube | Video | General public |

| La caída del muro del cáncer | — | General public |

| Libertaddigital | Video | General public |

| Elmundo.es/especiales | Photos | General public |

Source: Compiled by the authors

We do not have to add any exceptions to the web page model we have been using so far. Except on Monografías.es and Informe Semanal, visitor numbers are not provided. The former indicates that Like [Me gusta] has been clicked on 47 times. The Informe semanal video has been recommended 34 times. Three websites provide links, all of which are internal, except in the case of Wikipedia. Of the four sites which carry advertising, two are newspapers (libertaddigital and lainformación.com) and two are specialised sites (El Historiador and Monografías.es) which are targeted to students.

There is still no bibliography (except on Wikipedia which even provides a filmography), nor any forums: this confirms once more that this is not normal practice on this type of website.

3.8. The image of the fall of the wall on the internet

In this case, there are no interactive elements or comments from users either. The Wikipedia page has scored a rating of 4, and the remarkable feature is that some 390 people have voted, which is a clear sign of its primacy as first choice for information.

There is direct access to the information on all of the pages, but users can open different tabs on the Redescolar page as well as within the special reports by El Mundo and La información, enabling them to select what they are interested in and the order in which they wish to access it.

In terms of the content, neither El Historiador nor Libertad digital provide information directly related to the search. The former reproduces an article from the daily newspaper Arriba which was published three days after construction of the wall began. Libertad digital reproduces an interview with Francisco Frutos, leader of Izquierda Unida, which talks about the fall of communism and is dated November 5, 2009.

In short, of the 11 webpages listed on the first screen of Google results, only seven contain information which is directly related to the search (or allow you to access that information). Four sites (Wikipedia, Redescolar, La Información and El Mundo) offer fairly complete information: the political situation which led to the construction of the wall is explained first, in order to move on to commentary of its fall. As in the previous examples, Wikipedia is the one that offers the most complete information: even including the detail of the press conference at which Schabowski announced the immediate application of the travel law, i.e. the opportunity to leave East Germany. However, Monografías.es explains the causes more fully, including both the background relating to German domestic politics and the international political context.

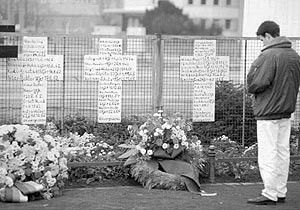

In terms of the audiovisual material, the montage by La información stands out because of the way it has been produced, as well as its clarity. There is no voiceover: the explanations are given in titles which allows the strength to lie in the image. It gathers the testimony of various (Spanish) journalists. Informe semanal reports on the events just a few days after they happened (the programme is from November 11, 1989). The narration therefore lacks the reflection and perspective that the subsequent course of events would have allowed. The majority of the photographs used by El Mundo come from agencies (such as Reuters, AP). Very little text is used and there is a particular focus on the emotional aspect of the events (see Photo 2):

Photo 2. Photograph included in El Mundo.es, “The wall that divided Europe”

REMEMBRANCE | The happiness could not be complete, however. For many Germans, November 9, 1989 came too late (AP)

3.9. Why did the wall come down?

The factors which contributed to the wall coming down are simple according to the internet. Wikipedia points out the demands for freedom from within East Germany: there were mass demonstrations against the government and there were constant escapes via the embassies of Czechoslovakia and Poland, and through the border between Hungary and Austria.

Redescolar attributes a leading role to Gorbachev and to international pressure[10]. Monografías.es makes it clear that this event did not occur spontaneously: “On the contrary, it is rooted in countless events in German daily life as well as international politics.” It gives great importance to the opposition organisations within Germany, which the other websites do not mention.

As we have seen, within each of the searches we have found different versions of the events being analysed, with the exception of the commemoration of Europe Day.

-

The European Union on Wikipedia. Elements for reflection[11].

In this section our analysis focuses on comparing the information offered in various languages by Wikipedia, about a particular concept which is of continent-wide relevance: the European Union. The quantitative analysis has been limited to simple elements which are easy to find: length of the initial explanation and the extent of the broader information which comes later, measured in units of information (sections and subsections that appear in the index). We are aware that these elements are very basic, but they appear to be sufficient to enable us to come up with an initial approximation.

4.1. The versions on Wikipedia

Analysis focused on the information supplied in Castilian, French, English and German. Given the particular interest that it offers in the Spanish context, we also turned our attention to the corresponding versions in Catalan, Galician and Basque.

The first consideration is that the fullest and most detailed information – within the context of generality implied by this net-based encyclopaedia – is provided in the Castilian version. The introduction to the Castilian version contains 37 lines of information compared with 20 in the English version and 26 lines in the German and French versions. The German and English versions are very similar in terms of length and information. Perhaps this introduction is an indication of the differing importance that the European Union has for each country: for France and Germany, it is part of a continual process which they have been involved in from the very beginning. Spain had been pursuing membership of the European institutions for decades, and therefore accession was an essential and very long-awaited event; a real success. In contrast, it is not even clear whether Great Britain considers itself part of the European Union.

The scope and detail of the rest of the information is also uneven: we have measured it in units of information based on the index which is given for each version: history, culture, territories, languages, institutions, treaties, demographics, etc. Once again, the Spanish version offers 54 units of information compared to lower numbers for Great Britain (38) and France (48), and a more similar amount for Germany (52). The German version is offers the fullest and most detailed information on the EU itself, without digressing on to the details and peculiarities of Germany (whereas the other versions do focus on their own national cases). In other words, the German version is the most attentive to the EU.

Thus, it is interesting to note that in the text about languages, the Great Britain version dedicates a relatively long section to those which are not official languages of the EU, but are tolerated in that any citizens who speak them can correspond with the European institutions in that language. This does not occur in the Spanish, French or German versions.

It is also interesting to note that the English version offers a list of the most widely spoken official European languages, with statistics on the percentage of people who are native speakers as well as on the number of EU citizens who speak those languages. This is significant because although German is the most widespread native language, English is (by a long way) the most widely known and used by EU citizens.

Other information given about the EU also varies from version to version. For example, the Spanish version dedicates two paragraphs to the recognition of same-sex marriages in the EU and highlights the leading role played by Spanish legislation. The version for Great Britain merely points out that in the EU there is no discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. The French text states only that human rights form the basis of law in the countries of the EU. The German version does not even mention the subject.

4.2. Non official languages and domestic nationalisms

The differences between the versions which are offered in Catalan, Basque and Galician (the three co-official regional languages in Spain besides Castilian) contain some interesting novelties in comparison to the Castilian version, but that does not mean they are original. Firstly, the texts which precede the index in the Galician and the Catalan versions are of almost the same length and contain very similar ideas. What is interesting is that both of them clearly depend on the introduction given in the English version since they are of a similar length (Catalan version 20 lines, Galician 21 and English 20). The explanations which come later differ in length however: the English version is the most complete (38 units of information) compared to 25 and 22 in the Catalan and Galician versions respectively. The Basque version is extremely simplified: the introduction to the term ‘EU’ takes up 9 lines and the subsequent explanation consists of just 11 units of information.

As we had assumed, the greatest difference was to be found in the references to the languages of the EU: the Castilian version does not mention any of the co-official Spanish regional languages explicitly, although it does point out that there are 150 regional languages within the EU which do not hold official status. This takes relative importance away from Catalan, Galician and Basque, which do have a certain official status. The Catalan and Galician versions dedicate 4 paragraphs and 21 lines to their explanation of this aspect of the EU. What is of greater interest is that they are very similar to each other and both depend heavily on the text of the English version, which dedicates a similar amount of words to the subject. The English version mentions Welsh and Scottish Gaelic as languages which are not official in the EU but have a special status: people who speak them can correspond with the EU authorities in their own language. The same applies to Galician, Catalan and Basque, and for that reason these are mentioned explicitly in the English version as well as the Catalan and Galician versions. It is very likely that this is an agreed text with versions in each one of these languages (except in Basque). The English and Catalan versions point out that although the programmes of the EU support these ‘unofficial’ languages, it is the member states who are assigned with the protection of linguistic rights in each country. The version in Basque simply presents a full list of the official languages of the EU and another of the non-official languages with around 20 entries: these include the six mentioned previously.

The Catalan version emphasises its interest in the Catalan language and desire for it to become established in the EU by adding two pieces of information. Firstly, it reproduces the list of 23 official languages featured in the British version, with the addition of Catalan. It also adds the fact that Catalan is the mother tongue of 1% of the European population (like Slovak) and that, furthermore, 2% of the population of the EU speak it as a second language (like Danish). This is a clear means of demonstrating that several of the official languages effectively have a smaller presence. There is one final and very significant piece of information. In the unit of information “Most important historical events,” the Catalan version gives a list of five dates. The last is November 16, 2005, when the presidents of Catalonia and Valencia addressed the EU “Committee of the regions” in Catalan. An indication of the Catalan governments’ determination to promote the use of their language on the net can be seen in the heading which appears at the top of each of the pages in Catalan on Wikipedia[12].

In this section we have dealt with a few examples of how a source of information like Wikipedia can provide useful profiles for historians to use in their research. We could conduct very similar analysis of high circulation publications (for example text books for primary or secondary school pupils). Such publications and Wikipedia share an enormous potential to enable historians to evaluate processes and events. Firstly and quite simply, one could investigate whether these texts include or omit a particular term from their catalogue. Of course we should remember that on Wikipedia an omission or inclusion can always be corrected by any interested party. The length of the text devoted to each term could act as a second filter for the historian. In this case too, the initiative of an individual can rectify oversights or omissions. The focus and selection of events and processes dealt with is another factor worthy of consideration. These questions are of most interest in relation to terms which describe broad historical processes or define institutions.

For those who consult Wikipedia regularly, it is of equal importance to consulting a printed encyclopedia in the past. If you are looking for a basic piece of information, the aspects described above usually go unnoticed, and therefore Wikipedia is equally important for historians as the printed versions were and continue to be, since it allows them to analyse the construction of the collective image, consolidated opinions, prejudices, myths and mind-sets.

-

Spanish history forums.

Our analysis centres on two different Google searches. The first search carried out was for “Spanish history forums”[13], and the second for “Forums about the Spanish Civil War.” This fine tuning is key, since our emphasis on the first page of Google results leads us, by definition, to the most popular forums, and consequently to those which are of least interest to specialists in history, or even for specialists in a specific aspect of history, (in our case this specific aspect was the “Spanish Civil War”).

We have excluded forums for professional historians from this analysis since they are completely different to the popular forums on historical matters which attract the most visitors. In terms of numbers of visits, the most popular forums for Spanish speaking professionals are probably the ones hosted on the La Historia a Debate (http://www.h-debate.com/) platform. However, they do not appear when you type ‘history forums’ into Google, even if you leaf through the first twelve pages of results, despite the fact that the aggregated user figures are astonishing.

The first screen of Google results for the term “Spanish history forums” offers seven links. Logically, each of them deals with a very specific aspect of history. Some of these links can be slotted into conventional spaces of historiography (and the sphere of military history in particular). Others simply deal with the recent background of a topic which is currently in the news (from Formula 1 to video games, via football).

Participants in these forums are not professional historians, but rather amateurs and scholars who exchange information about their favourite subjects. However specific these participants’ interests may be, we can include them in the broader group of history enthusiasts. On other forums, the sole aim is to gather information about a particular phenomenon, even if, as in one of the cases, users do not seem to have a very clear concept of what history is[14]. Otherwise, these military history forums seem to be aware of the purpose they serve in reality, which is to satisfy the shared passions of their members[15].

As in many face to face conversations between people with shared interests, every now and then the subject moves far beyond the initially stated aim and the focus switches to another area of current affairs, as a group of people who share one hobby usually have others in common too. A typical example is offered by naval history forum Todoavante, on the subject of a website competition organised by the Spanish Ministry of Defence. Forum participants complain vociferously about the fact that they were not awarded the prize, and this subject takes up by far the most space as well as the most messages on the forum. It is easy to imagine a roomful of retired Navy sailors, proud of their knowledge and ability as a military and technical corps, with a shared project (building a webpage to win the competition) and their conversation eventually turning to the competition despite the fact they had met up to talk about other subjects. A similar example is provided by Foro Militar General, which is also home to fierce debates about current day politics. Since June 2006, topics have included the possibility of a referendum on the right to self-determination in Catalonia, opinions about the government, and the Chilean President’s policies.

Perhaps those forums in which retired professionals take part could be considered virtual adaptations of traditional meetings. The virtual version can reach wider audiences because of the level of convenience it offers, even for users who may only have a basic knowledge of the tools required (going onto the net, sending and receiving messages, uploading and downloading text documents, photos and videos).

Military history dominates the forums about classic historical subjects. Although it appears to be less active than ones listed later, top of Google’s list of suggestions is a forum about naval history (Todoavante). Its scope is not limited to battles (it includes information about the technical specifications of ships, biographies of illustrious mariners, photos, book reviews, links to other websites, etc.) but most of the contributions do refer to them. Participants seem to be naval officers, not historians. The site also features a blog which was started in February 2007 and is kept up to date.

The second entry for military history forums on the results page is the Second World War. Within this general subject there is discussion about biographies, espionage, uniforms and medals, theatres of operation, air, land and sea forces, political, economic and social subjects, etc., and supporting documents are provided. A broad, generalist section entitled Miscellany is the most popular with almost 40,000 messages. This volume makes it impossible to monitor. The specificity of its subject areas is curious. For example, there is a discussion of the pros and cons of the wheels in crawler tracks in German tanks. Some subjects are almost macabre. In a debate about Hitler’s relationship with Eva Braun, a user comments that Hitler had halitosis. The statement raises questions, and proof and documentation are requested… other webpages are offered as sources. Discussions go on for around a month. The reader gets the impression that this is a competition as to who can unearth the most curious fact. A few book reviews are presented.

The third forum of a historical nature is ‘The great Captain’s forum, military history.[16]’ It tackles a variety of thematic lines: ancient and medieval military history, modern and contemporary military history, the First World War, current military conflicts, special forces, militias and terrorists, etc. The section on general military history attracts the highest level of participation, featuring almost 700 subjects and 20,000 messages. Within that section, “Paintings, prints and images of the Second World War” contains the highest number of posts (some 3,000). The thread was started in March 2012 and remains open at the time of writing (September). What is surprising is that the majority of contributions are made by the same five authors – basically five enthusiasts who have collected images and made them available to others on the net.

The fourth active forum of this type which appears on the first page of Google results is entitled General Military Forum[17]. More than 35,000 subjects have been covered since its creation and it receives almost 400 posts a day. These figures would suggest that it is a platform on which the opinions of the Spanish military world become apparent. It describes itself as being “a moderated forum for the civilised discussion of the air forces of the world, military history, soldiers and their weapons, defence and security”. Historical subjects have less weight than on the other forums and political discussion appears to be one of the essential elements, as we have already pointed out. Its initial list of subjects offers: Armed forces of the World, Spain and Latin America.

The first page of Google results for the second search term– Spanish Civil War – provides interesting clues to begin with: the forums are non-academic in nature and are used by a massive number of enthusiasts who specialise in specific, often relatively minor, aspects of the conflict (the Northern Front, for example) [18]. This impression is confirmed by some of the other forums, including el Gran Capitán.

These forums about the Civil War are a meeting place for enthusiasts of the subject. They do not usually focus on general questions, but there is no shortage of very precise political viewpoints which can be seen as continuations of those held by the sides who fought in the conflict. Political condemnations are the order of the day in the rare disagreements which occur. It is not always thus. The subjects of conversation are specific, but, at times, the degree of specialisation is enormous. For example there are thousands of messages accompanied by photographs, plans, location maps and commentaries on the “archaeology” of the Civil War, particularly fortifications (parapets, bunkers, machine gun posts, etc.) The collection of information about these aspects – or in general about photographs, whether they belong to individuals or institutions, are widely known or previously unpublished- is vast. On one hand, these examples have the usual disadvantage of forums, which is that searching them is extremely difficult. On the other hand they also share their greatest advantage, by contributing documentation that would otherwise be lost.

As was the case for the previous group, there is hardly any academic presence on the forums about the Civil War. Interventions are commonly made by people who are experts on the more remote aspects, such as types of weapons, very specific military units, little-known personalities, fortifications etc., making use of this enormous knowledge. Conversations are normally driven by just a few individual users. Reading the content gives the impression that a very small number of amateur researchers and true experts are responsible for more than 75% of the contributions. This founding core rarely consists of more than a dozen people. For example, in a forum about the battle of Brunete there is little discussion on the wider significance of the battle, but there are hundreds of posts about specific episodes, photographs of the town and the ruins as they are today, some photos from before the battle, lists of the dead and injured on each side, etc. As always, the biggest problem is the critical use of the materials and access to those which could be of real interest to a researcher.

Lastly, what use do these forums have for historians? The first is the opportunity to access difficult-to-find material about a particular aspect. In the forums about the Spanish Civil War, one often finds references to books, scanned pages from books which cannot be found easily, and even reproductions of original documentation; not to mention the photos. Other times they can be of great use in outlining research. Several participants in the forum put people in contact with an author who was doing some very thorough research into personal correspondence during the Civil War[19]. At times, without the selfless and enthusiastic collaboration of several participants on Civil War forums, the research would not have been possible. It is likely that other projects have received similar assistance. Though forums can never constitute a main source, they can help to fill in the more obscure or previously ignored aspects.

In summary, the specific forums used by professional historians are linked to networks which deal exclusively with that field. They play an unquestionable role in building research networks, and a leading role in strengthening them. We could say that they facilitate the processes of exchange and internationalisation of research results; though they may not have overtaken the old postal networks in qualitative terms. In another order of things, though still within the realm of the historian, we should not forget that there are several international publications which still require that originals are sent on paper for evaluation, and that the old procedures live on more than one might expect.

Another interesting point is the consideration of forums as a historical source in their own right. This would take us into another line of study, which would be similar – though of course not equal – to that of the use of the media as a historical source.

-

Discussion and conclusions

Wikipedia’s absolute dominance as the first choice source of information in the field of modern history has been confirmed, and could probably be extrapolated to history in general. Despite its limitations and the criticisms levelled at it by the academic world, it is important to point out that, among the results on the first page of a Google search, Wikipedia is often the most complete option from which to obtain initial information. Of course it is possible that Wikipedia is the first page Google offers by default. In any case, in a system of searches where the key criteria are highest number of views, quantity of links and relevance to the subject searched for, it is not surprising that Wikipedia consistently appears as the first ranked option for information.

It is clear that the non-specialist user can contextualise and gain initial information about the event they are looking for through this service. What it offers is also of interest to the armchair historian: there are direct links which allow the expansion of particular aspects and it is the only website of those analysed to regularly offer a bibliography and even a filmography.

On the other hand, Wikipedia is open to abuse by interested parties as it is based on the concept of collaborative work. In theory, debate between the editors should filter out this activity. In practice, few individuals can compete with an institution which commissions the writing of very precise information in any Wikipedia articles it considers to be sensitive to its interests. The case of the non-official languages is just one example.

Another notable feature of this tour of the first page of Google search results is the presence of pages which are aimed at teachers, and designed to facilitate their search for teaching resources about specific subjects for younger pupils. This suggests that school teachers are the group of professionals who use the net most frequently in the course of their work. This is backed up by the fact that there are relatively plentiful resources and spaces dedicated specifically to them.

Since the school teachers’ account focuses on the basics and lays down the facts, the differences in information provided to explain certain events are less important to them. Teachers are also the group which can most easily determine the quality of this information and choose what they deem to be most appropriate. Furthermore, their daily work does not demand monographs or great detail. Thus, the net is a very useful instrument for their ordinary, and even extraordinary, professional activity (for example talking about a civic celebration such as Europe Day, at the request of the education authority).

However, the majority of searches seem to be made by people who do not have any particular interest in education. The average user of this type of search is a regular person, with a basic education, who just wants to access a piece of information which is interesting (or important) to them for some reason: from school questions asked by children and grandchildren, to names of people and events which have appeared in the media.

As we have seen, these searches direct the user firstly to Wikipedia, but it is interesting to point out that online versions of the news media feature on all of the first pages of Google results. In other words, the press maintains credibility as a source of information for the general public. The net facilitates these searches (at least for the time being and while they are free to access).

An internet search is usually referred to in terms which denote speed (Navegar in Spanish, Browse in English), and give the idea of flitting from one piece of information to another. The links provided are key to this, since they direct the user towards supplementary information which can range from original documents (not very often) to a more detailed explanation or contextualisation (more frequently). The latter are not always directly related with the initial search. In any case, the abundance of links facilitates quick and additional searches for a curious user who is looking to fill in any gaps in their knowledge quickly.

The fact that you do not have to leave the net, or carry out complex tasks (such as specialised searches in online libraries, databases or directories) is an enormous advantage for an audience with no specific education in history that simply wants to clear up a question, plan a trip or help their children with their homework.

The most tangible weakness of these first search results is the lack of interactivity and the poor multimedia offering. It is likely that the written tradition and the reference format still weighs heavily on the authors of these web pages (i.e. printed encyclopaedias influence Wikipedia for example). Furthermore the best quality, professional images are usually subject to copyright and only the institutions and the media can provide them. The amateur nature of many of the images which circulate on the web mean that authors are not keen to use them to illustrate or contextualise a piece of information (except in very rare cases) when they are looking to offer reassurance as to its veracity and reliability. Furthermore, a truly interactive website demands a level of attention and professional specialisation which not all institutions, media or general websites are in a position to dedicate. In this case, and as our results show, the best option is not to offer the opportunity for interaction.

In summary, general internet searches about history seem to share some limitations and advantages with sciences and other areas of academia. While the big advantage of internet searches is the enormous capacity to spread information, they also retain almost all of the disadvantages of traditional media in terms of informing and educating people. On the internet, these advantages and disadvantages are magnified given the easy access to the content.

Notes:

[1] http://kico.es/los-200-criterios-que-usa-google-para-elegir-el-orden-de-las-paginas-web. Consulted September 8, 2012.

[2] Respective search terms in original Spanish: Historia de la Unión Europea, Willy Brandt, Conmemoraciones: el Día de Europa, La caída del muro de Berlín, Unión Europea

[3] In our view, a link from one page to another implies that the former is giving a vote of approval to the latter.

[4] Cápsulas históricas has 27 “Likes”; 2 “Dislikes”; the video about the History of the European Union by Israel González, 6 “Likes”; Rincón del Vago, 7 “Likes”.

[5] The lower the number of clicks required to obtain the desired information, the better the accessibility

[6] For example on October 26, 2004. It reads: “The President-designate, José Manuel Durão Barroso, withdraws his proposal for the new European Commission. It is hoped that he will present a new proposal to Parliament for approval in the following weeks”. There is no mention of why Barroso had to withdraw his proposal.

[7] Bachillerato is Spanish post-16 education, equivalent to A-Levels/Baccalaureate.

[8] By September 3, 2012, it no longer appeared on the first page of Google results.

[9] In April 1937 he arrived in Barcelona for a meeting of the International Bureau of Socialist Revolutionary Youth Movements. The meeting was interrupted by the barricades on May 3rd. Brandt managed to get out of Barcelona aboard a foreign boat.

http://www.fundanin.org/Labatalla1969R.htm (consulted on September 5, 2012)

[10]http://redescolar.ilce.edu.mx/redescolar/act_permanentes/historia/html/caida_del_muro/murodeberlin.htm, consulted September 7, 2012.

[11] The entries consulted on September 6, 2012 were:

European Union (in Spanish) on Wikipedia: http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Union_europea

Catalan:

http://ca.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uni%C3%B3_Europea

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/en/treaties/dat/12002E/htm/C_2002325EN.003301.html#anArt150

Galician:

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/en/treaties/dat/12002E/htm/C_2002325EN.003301.html#anArt150

English:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Union

French.

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Union_europ%C3%A9enne

Basque/Euskara:

http://eu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Europar_Batasuna

German:

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Europ%C3%A4ische_Union

[12] Not surfed the net in Catalan yet? Discover how you can ‘Catalanize’ your computer

Original: ‘Encara no navegueu en català? Vegeu com podeu catalanitzar el vostre ordinador.’

[13] Search terms in original Spanish: “Foros españoles de Historia” “Foros sobre la Guerra Civil Española”.

[14] In a post on Foro Punk about the 10 best footballers in history, one of the participants asks if history refers to the last 15 years or more.

[15] A Foro Militar General user states in a post that his participation has to do with his “passion for history”.

[16] Name in original Spanish Foro El Gran Capitán. Historia militar

[17] Foro Militar General

[18] http://guerracivil.forumup.es/memberlist.php?mforum=guerracivil

http://www.militar.org.ua/foro/guerra-civil-espanola.html

http://www.elgrancapitan.org/foro/viewforum.php?f=7

http://guerracivil.mundoforo.com/

http://www.gefrema.org/foro/viewforum.php?f=17

http://www.fotosmilitares.org/viewforum.php?f=31

http://forohistoria.creatuforo.com/armas-usadas-en-la-guerra-civil-espaola-foro32.html

http://www.guerracivil1936.com/web/index.php?option=com_wrapper&Itemid=2

http://www.boards4.melodysoft.com/app’id-guerracivilnorte

http://www.foropolicia.es/foros/guerra-civil-española-t81736-165.htlm

[19] Cervera Gil, Javier, Ya sabes mi paradero. La Guerra Civil a través de las cartas de los que la vivieron, Planeta, Barcelona 2005