History and WEB in Slovenia

Updates

2014 (web) | 2016 (web) | 2016 (tv) | 2017 | 2018

by Martin Pogačar

Introduction

In this research I look from a post-socialist Slovenian perspective at several ways and approaches in which Slovenian history is re-presented, remediated, re-narrated, re-contextualised online, i.e. in digitally mediated environments. I focus on a selection of vernacular interventions on YouTube and blogs and interrogate the ways the past is re-purposed and how re-interpreted in the processes and practices of revision of the 20th century seminal events and periods. With this I primarily refer to the World War II, anti-fascism and resistance, perceptions of communist period/regime and the post-socialist transition, which feature as a recurring topic in may online interventions. These topics are approached here from a specific position significantly defined by the present European complexities, the legacies of the 20th century and the social, cultural, economic and political transition that was more or less successfully (self)imposed on the former Eastern European communist countries. In this regard, the post-socialist perspective is a crucial defining factor of the research as it engenders an approach to the European past(s) through processes and discourses of ‘democratisation’ ‘returning to Europe,’ ‘belonging to Europe,’ ‘post-socialism,’ ‘freedom,’ ‘capitalism,’ etc. all of which importantly shape contemporary discourses on European and EU pasts, presents and futures.

In the following I first delimit the research field and methodology: the vast research area as the digital media ecology (DME) is, an all-encompassing approach is not viable, particularly considering the ephemerality and scale of online communications and representations. True, large-scale analyses as for instance proposed by the software studies approach, i.e. to follow greater patterns based on massive quantities of data might reveal certain trends in ways people/users react to and make sense of events in digital environments.[1] However, I propose an approach that, admittedly has it limitations, but one nevertheless still that focuses on a ‘manageable crowd’; although it might skew the interpretative picture somewhat, it nevertheless gives much more room to see and qualify individual expression, affect and acknowledgement of singularity embedded in universality.

Therefore, in line with the principles of ‘hovering attention,’[2] I interrogate in the second part a selection of YouTube videos and two blogs, that in their particular approaches deal with re-presencing[3] the Yugoslav socialist past with a view to articulate concerns about the present and future. This calls for a multimodal discourse analysis where the objects of analysis are seen as the loci of (vernacular) historiographical, but also socio-political, action which on the one hand co-creates, distributes individual/intimate audiovisions of the past, but on the other also mobilises, manages and deploys content and action in response to the present by re-presencing and re-interpreting the past.[4] This practice is underpinned by media archaeology[5] and the practice of vernacular digital archiving.

The results of the analysis are synthesised in the discussion on the prospects of negotiating the diverse/contested pasts and pluralities of their present interpretations online, with a view to their mobilisatory, emancipatory potential in view of the possible (European) futures.

When I was thinking how to approach the vast topic of history on the internet I realised it was in any case an overwhelming task. Mostly due to the ephemerality and perpetual ebb and flow of content washing up and retracting back into the depths of the non-existence (Page Not Found – Error 404). Therefore I decided to trace and investigate online activities related to Slovenian past and history through the lens of two events that importantly marked the 2012 culturo-socio-political scene in Slovenia: the celebration of the Statehood Day (26 June) and the Day of Restoration of the Primorska Region to the Motherland (15 September). As limiting as this may seem, it may nevertheless prove useful in the long run: this report will provide a micro-slice of what topics mattered at a very specific time in a very specific place. And in very specific socio-cultural and political situation at the end of 2012.

In the time when many national enterprises (and I am not talking about business and economy here) are in danger of becoming fully privatised, the story of European past(s) and future(s) is often sidetracked by incessant obsession with saving the present. What is more, the interest in the past is often discarded as archaic, degressive endeavour unfitting the present moment. The lessons from the past and the driving force (mobilisatory and emancipatory potential) of the engagingly articulated possible futures are in such atmosphere easily forgotten. The logic of bare survival discards anything that has no imminent ‘value,’ which hardly gives room for a playful engagement with stuff historical, national, individual, European etc., outside the strictly cost-benefit scope.

When looking at the processes of Europeanisation, (re-)nationalisation, de-collectivisation, radical individualisation and disturbing atomisation and dis-empowerment of individuals and collectivities, one should bear in mind that a critical approach is on order, if a way is to be found out of the obvious economic, cultural and political impasse, if the ironies of history be transformed into the potential to vocalise, articulate, empower and (re)assert the human, human dignity, human rights and, yes, utopia of a better world. Alas, as Tony Judt said, we live in a time where imagining alternative futures collectively is almost impossible (or actively discouraged).

Now, at this point I propose to see the digital media ecology, social networks and online action as a tool, technology and practice that effectively enable externalisation of discontent and bypass the sanitising and sanctioned discursive spaces of ‘classical’ communications channels. Moreover, it is a tool that can often be regarded as one that enables the transformation along the silence-noise-voice line, i.e. its technological characteristics and cultural uses, in the ideal situation, enable transformation and articulation of individual, alternative, guerrilla initiatives, deliberations and interventions.

With respect to the questions concerning the European divided pasts in relation to post-socialist presents and interpretations of socialist past, the digital media can and are used as a tool and a space where ‘transgression’ and contestation of official state-sponsored interpretations can be enacted.

*

Before moving on to explain the rationale of my research, an sketchy illustration is in order of a broader situation the post-socialist societies found themselves. The 1989 fall of the Berlin wall is today often seen as the one historical event (or rather a culmination of events) marking the end of the Cold War and having supposedly lifted the Iron Curtain and opened the path to freedom and democracy to the Easternites. As it has been made clear in the almost 25 years after the event, the symbolic wall still stands tall, firmly dividing the ‘wild East’ from the ‘proper’ Europe, democracy and freedom, market capitalism etc. Mostly in terms of ‘maturity’ for democracy: the East’s capacity, readiness and capability to form a democratic political system and society is systematically questioned, if not outright denied. And this, it has to be noted, is a two-way process: in post-socialist catharsis the East readily denounces itself any democratic competence.[6]

What is worse, the post-socialist societies, as Boris Buden argues, are victims of ‘repressive infantilisation’: ‘people who in democratic revolutions of 1989/90 proved they are politically mature, were overnight turned into children … people who themselves fought for their freedom must first learn how to truly enjoy their freedom.’[7] This condition is not entirely externally imposed, but is rather to a significant extent administered internally: adopted by political elites on a mission to exorcise their respective socialist pasts.

On these grounds, the Easternites are denied the freedom to fully exercise their newly acquired freedom. They live in the aftermath of a ‘“catch-up” revolution’ where they ‘are at the same time rendered immature and condemned to blind imitation of their caretakers, in ludicrous belief that this is the way to achieve autonomy,’[8] rather than accepting the complexities, dissonances, perplexities of their own, albeit socialist, past(s). This is all the more disturbing, if we see the post-socialist condition through transitionality or transformation, concepts that cannot do justice to what is going on in post-socialism; in fact, these conceptualisations, which are most straightforward derivatives of mythology of transition, in this case overtheorised and over-emphasised, deny historicity and epochality to the post-1989 condition all over Eastern Europe.[9]

This now brings me to the rationale and the set-up of the research. The post-socialist reality seen through this perspective calls for a critical re-evaluation, de-denigration and re-appraisal of certain aspects of the socialist past, for a recognition of values that may not have been fully realised (or not at all), but nevertheless stood prominent in the socialist emancipatory project (and seem to be painfully absent today). Analysing the cases of remediation of Yugoslav past in Slovenian post-socialist present I look through the perspective of two events that resonate throughout the latter half of 2012: Statehood Day celebration and Day of Restoration of Primorska. This perspective enables me to look at the practices, processes and (political and vernacular) discourses of democratisation, de-totalitarianisation and ‘independentalisation,’ and at the same time also discern the politics of emotion apparent in dealing with the past online. All these discourses are decidedly marked by radical reinterpretation of the (1941-) 1945-1991 past.

Setting the research field

Before going into this, however, I need to explain the research field parameters. The vast field as the DME is, the internet in particular, an all-encompassing approach is not viable. Therefore, according to the principles of ‘hovering attention’ I interrogate a selection of YouTube videos and two blogs. The ‘genre approach’ facilitates insight into the transience and migratoriness of content and at the same time also reveals different approaches and strategies engendered by different genre-technologies.

The initial selection of the cases was based on Google search by keywords: ‘komunizem socializem slovenija evropa,’ ‘slovenija, evropa,’ ‘26 junij, proslava,’ ‘15 september.’ The keywords were chosen as entry search words and tags that might yield results related to the problematic. Clearly, the algorithmic nature of search engines and metadata searches cannot effectively filter out irrelevant results, but decidedly filters search results based no my previous searches. Quantification (word counts, frequency of phrases) was deliberately avoided as it seems more profitable, as explained above, to rather focus on the ‘feel,’ emotion and affect contained and conveyed in the analysed content; still, some quantification is nevertheless useful, i.e. number of views, comments, links, shares etc. as it gives some idea about the ‘impact’ of the content in question. Avoiding quantification, i.e. statistical analysis of frequency of certain phrases and words in my belief does not hinder relevance and credibility of the research.

YouTube: On YouTube I look mostly at videos (e.g. digital memorial videos) as vernacular interventions that through remediation of audiovisual and textual media content (original footage or digital born) co-create highly individual(ised) visions of the past. The analysis also entails some other videos, e.g. excerpts from TV programmes, but in this part pays particular attention to comments and other attributes that reveal affectivity. Multimodal discourse analysis, including audiovisual analysis and analysis of tags, video statistics, descriptions and comments will provide central analytical focus.

Blogs: In this part I look at a selection of blogs by several users who post about historical topics and also engage in political commentary. The nature of blog analysis is somewhat less dedicated to audiovisual and rather focuses on writing, style and content. At that I look at both the post and comments from where I trace the politics of emotion and engagement on the part of the blogger and commentators.

Multimodal discourse analysis

The three distinctly individual, yet also significantly interrelated medialities, indeed vernacular remediations and renarrativisations of the socialist past in post-socialist presents, essentially a result of a co-creative action undertaken by individual users, are approached as cases of digital storytelling.[10] As such the analysed objects establish the core subject of analysis: multimodal mobile media objects (4MO): objects that may be shared, embedded, circulated among users and machines.[11] In this respect, particular attention is paid to the ways vernacular memory practices utilise digital technology and hence the 4MOs, with a view to the migratory nature of online content.

Digital storytelling is crucially enabled and conditioned by techno-cultural implications of DME and is importantly characterised by a) mobility of media objects and b) on-the-fly co-creative impetus.[12] This makes the investigated 4MOs the matter of co-creation and incessant permeability. To an important degree digital storytelling and digital narrativity retain continuity with ‘classic’ storytelling. The cases in digital storytelling (and memorials) are thus analysed qualitatively in the manner that can usefully be subsumed into the multimodal discourse analysis, as elaborated by Kay O’Halloran, who sees it as ‘concerned with theory and analysis of semiotic resources and the semantic expansions which occur as semiotic choices combined in multimodal phenomena.’[13] This enables to see the objects of study as non-hierarchical active parts in the production of meaning and hence ‘equal’ elements of the DME renarrativisations and remediations of the (socialist) past.

This approach relies on discourse analysis and entails analysis of audiovisual and textual elements which are investigated in terms of ‘technical’ utilisation of audiovision and text (the ‘what’ and ‘how’). In this view, the various ways the in which content is mediatised and remediated feature as an important aspect of analysis. The data are seen as ‘representations not of physical events, but of texts, images, and expressions that are created to be seen, read, interpreted, and acted on their meanings, and must therefore be analysed with such uses in mind.’[14] Moreover, the analysis also takes into consideration the very ‘migratory’ characteristic of representations and hence tracks the practice of co-creation as an additional aspect of content production and distribution. The analysis furthermore relies on ‘commentary textual analysis’ spliced with audiovisual discourse analysis. This approach facilitates insight into how the past is co-created (mediated/mediatised/renarrated) in DME.

A peek into the historical background

To give the reader a very general idea of where the research is situated spatially and temporally, let me briefly provide a general outline of the Slovenian history of the 20th century, a complex assortment of shifts and changes, ideological, symbolical and geo-political. A part of Habsburg Monarchy inhabitants of what is today Slovenia entered the Great War on the side of Austro-Hungary and Germany, whose defeat against the entente left Slovene territory without about a third of territory and population. The 1920s saw the rise of fascism in Italy, which had considerable consequences for the territory that under the provisions of the 1915 London Memorandum became part of Italian Kingdom. The rise of Mussolini and his racist politics led to ethnic engineering in the Primorska region, where fascist authorities banned public use of Slovenian language, changed names and went as far as chiselling Italianised names onto Slovenian tombstones. At the beginning of WWII, Italy occupied Ljubljana (the Province of Ljubljana), while Nazi Germany occupied north and northeast, and Hungary northeastern-most part of what is now Slovenia.

This period is particularly important for conceptualisation of Slovenian post-WWII interpretation of the interwar period and the WWII, not least because during the war and anti-fascist resistance, civil war was unravelling between resistance formations (led by the Communists) and units that swore allegiance to occupation authorities. This ideological rift can be traced back to the rift between liberals and conservatives that has dominated Slovenian politics since the formation of first Slovenian political parties in mid-19th century.

The socialist historiography, in line with the message of the Nuremberg trials which clearly detected the guilty party in and for the war, initiated a construction of history, which explicitly understood liberation as a result of the resistance, and condemned the collaboration, ideologically and physically (in the aftermath of the war Yugoslav authorities were responsible for extra-judicial killings of members of collaborative units). Moreover, the entire post-WWII Yugoslav ideology rested on perpetuation of the socialist revolution, which was fuelled by Yugoslav geo-political positioning on the side of ‘winners,’ but was effectively carving out a space in between East and West.

This unique position enabled the country to actually follow a different form of socialism which brought modernisation, industrialisation, women emancipation, promoted literacy, established a system of public education and health service. On the other hand, the country was clearly totalitarian in that it restricted the freedom of speech, prohibited political opposition…

Now, 20 years after into the independent state the above mentioned events reveal developments, which show worrying signs of re-nationalisation, re-territorialisation and effective closing off of the public spaces for articulating dissent, alternatives or opposition. Of course, nationalism and historical revisionism in political and media discourses can be detected throughout the period and even before 1991 (across Europe). But at the same time, these processes unexpectedly provoked strongly articulated nostalgic practices and also a more critical, reflexive look upon the contested past and its absence in contemporary conceptualisation of the role of Slovenia, internally and externally.

Finally, 2012 was the year that saw another escalation of ideological treatment of the past and present. This was most obvious in the two events mentioned above that profess a high degree of ideologisation of contemporary Slovenian politics and society. At that it has to be said that to a significant extent this is corollary of interventions of two political parties forming the ideological core of the coalition. Nevertheless the fact that these events occurred, people’s reactions and continual attention, ab/use in the media say a great deal about the relevance and importance of the ‘inproper,’ unresolved past. This is why the media reverberations of these ideological interventions spur might prove the critical (if dangerously transient) repository of emotion and affect.

In the following I look at intriguing re-emergence of Slovenian socialist past online and interrogate the ways the past (particularly WWII and the post-war, socialist period) is dealt with today and to what purposes these events, directly or indirectly linked to the entire 20th century, serve. These cases prove fascinating spectacles through which the past is ‘translated’ into the present.

Vernacular digital memorials and other interventions on YouTube

A platform for publishing videos and at that also a platform for discussion, YouTube is a digital media environment that hosts a wide selection of audiovisual material. Cases interesting for this discussion can very well be termed digital ‘vernacular video memorials’ as they successfully exist at the interstices of a memorial in the classical sense and individual initiative. This is unique to DME and represents a crucial element in how the past is dealt with and represented online. The individual intervention in memorial landscapes could not have found a more present and diffusible medium. And it is for this reason alone that investigations of such videos prove revealing research objects.

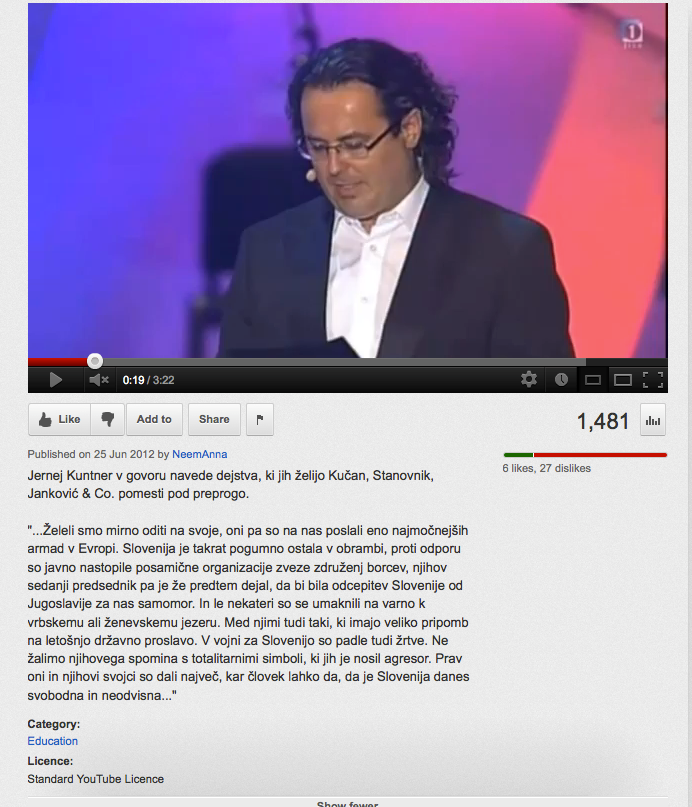

Despite the heated debates that the Statehood Day celebration, the preparations for the event, the formal addresses by the host and President of RS spurred in the media, very little can in fact be found on YouTube. Search term “dan državnosti 2012” yields several results, spanning footage from the event, from other events in Slovenia and several events in Serbia and Croatia. Despite the fact that there are literally no vernacular interventions, the footage nevertheless proves a trigger for people engaging in commenting, bringing into discussion the disdain of the way the ceremony was executed.

See: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8jhg_egnPY

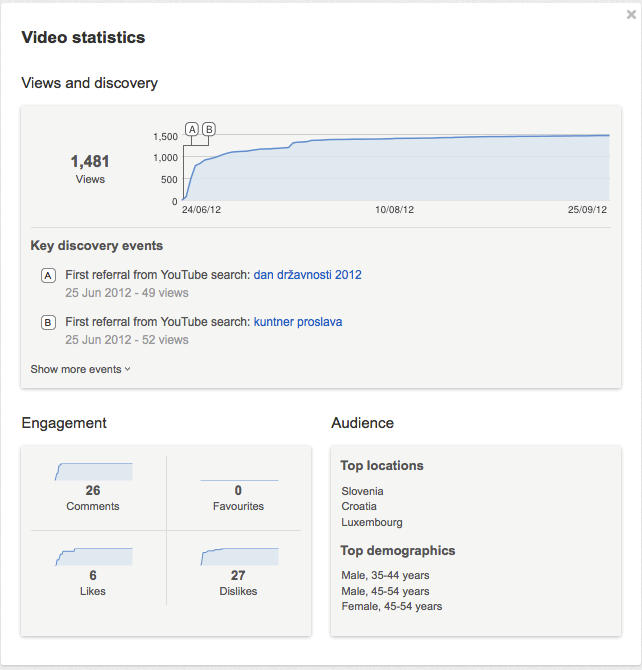

The 2012 ceremony was the first ceremony in over 20-year Slovenian history that was ‘cleansed’ of representatives of the League of Association of Combatants (Zveza borcev). Until 2012 they were seen as constitutive element in the mosaic of the Slovenian independence project. In the media and the public this has stirred heated response, as it was seen as revision of history and unjustified sanitisation of Slovenian history. Interestingly, this video seems to have elicited little response (at the time of writing, December 2012, last recorded comments are 5 months old). While it has been seen over 1,500 times, only 26 people have engaged in commenting, while 6 people liked the video and 27 disliked it. As unrepresentative as this sample may be, it nevertheless reveals a sentiment of disagreement with the way the ceremony was organised and the message it has given. With this I refer to excluding an important part of Slovenian history and reinterpreting the role of the liberation struggle: by ‘ousting the red star’ from the ceremony, the organiser (the government) effectively eradicated a constituent part of Slovenian history, while at the same time managed to revive and reinvigorate interest in both symbols and messages conveyed by the ‘red star.’

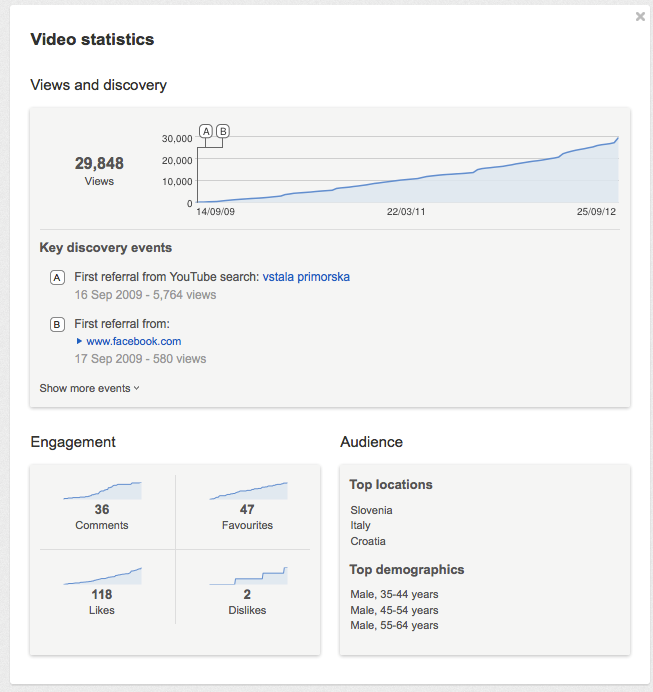

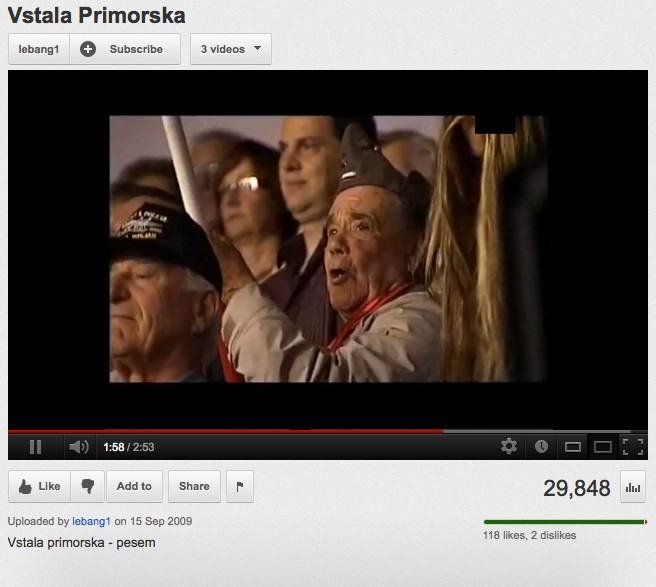

Similarly, there is not much activity recorded on YouTube related to the 2012 Day of Restoration of the Primorska Region to the Motherland Primorska celebration which was organised by the Koper municipality, apart from a selection of short clips featuring interviews. One clip explicitly related to the ceremony is from 2009, featuring a take from the official state celebration.

See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=agVaFXih8Vk&feature=related

The past is far from dead and much less so in an environment dominated by discourses of austerity and uncertainty. Then re-turning to the past comes as no surprise, and indeed, it seems that YouTube offers much more content that is not explicitly related to present-day affairs in terms of content, but proves as a site of emotionally engaged commentary of the present-day affairs. Videos abound, made by the principles of media archaeology,[15] that declaratively comment on the past, but in fact offer much more elaborate affective commentaries about the present.

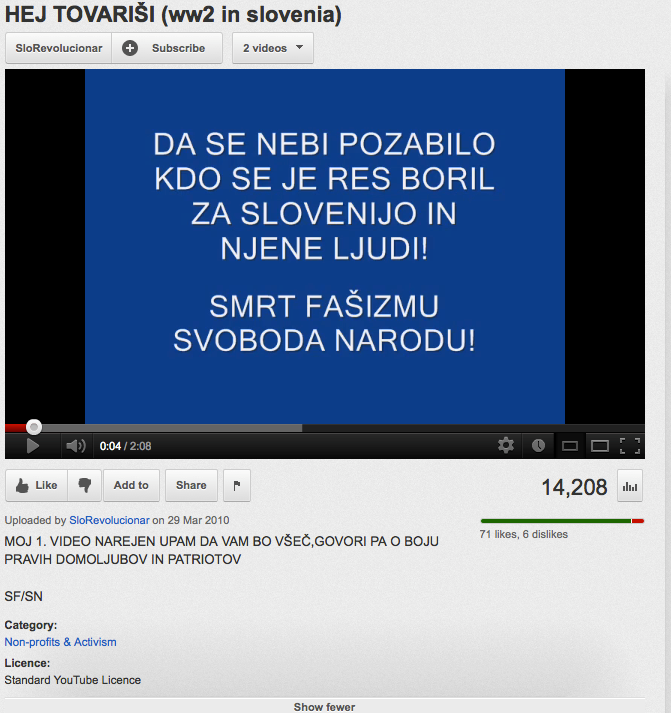

See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2rN0IEwytpw&feature=related

This video (vernacular memorial video), for instance features as a good example of digital storytelling and also as a case complying with the multimodal mobile media objects definition.

Translation: So we don’t forget who really fought for Slovenia and its people! Death to fascism, freedom to the people!

The author, SloRevolucionar, uses a popular song sang by the fighters during the war. The song became an important audio-marker of the war period after the war when it became the repertoire of partisan choirs. Later on it was even covered by several rock bands.

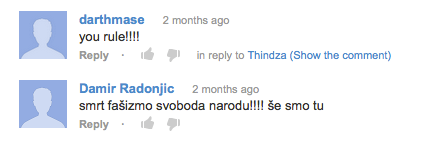

In this case, SloRevolucionar has used to song to dub a selection of photographs and images. Such renarrativisation plays mostly on audiovisual convergence through which a marching song becomes ‘inhabited’ by faces and images. Using also photographs showing ‘ordinary’ people in ordinary situations during the war endows the video with a certain degree of affectivity: the song and the images open a path into a different time, which seen from today’s perspective appears bereft of the everyday difficulties faced by people in the present. Despite the fact that the portrayed individuals were knee-deep in war, they are here seen as actors in the course of history. Retrospectively, their historical role is interpreted as part of an emancipatory project, which as the SloRevolucionar goes on to say that the country’s leader ‘ensured peace, normal life and jobs!!’. Particularly ‘normal life and jobs’ are common reference that when uttered explicitly express a statement about the present which clearly seems to be lacking normality and jobs. The video has so far been viewed 15.963 times (14.208 in early October, 19.720 in late December 2012) and has 30 recorded comments, which rarely go beyond expressions of dis/approval (for instance:

Heftier in terms of response, both in terms of quantity and content is for instance the following video ‘Partizanska pesem: Kdo pa so ti mladi fantje.’

See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aFNqd3LMXBg&feature=related

Made by GOBA23, this vernacular video memorial likewise uses audiovisual convergence, whereas the song is another once famous partisan song, “Kdo pa so ti mladi fantje” (Who are these young lads?). Again the multimodal mobile media object proves a site and trigger of affective response, and also provides some insight into the way the past is remediated, renarrated with reference to the present condition:

Translation: Death to cleric-fascism, freedom to the people! Myriam, I agree! Proud of our partisans and red. Currently disappointed with everything but still hoping for the best, if not today, tomorrow. We are getting sick of neoliberalism (economic).

@1969rainmaker

That’s right, Rainmaker, despite the present state, may the hope of a better tomorrow never fade! All young people (and their descendants) should always be accompanied by commitment to their homeland and the spirit of high national consciousness and love, as were our fallen comrades in their hearts and lives to in difficult times NLS [national liberation struggle]!

The most intriguing, however, are new uses of the past in DME that rely predominantly on referencing the past and introducing in the process an ironic stance. In many cases the users engage in reflecting on the past while making very clear the position from which they intervene. This entails making videos using popular music (as opposed to revolutionary, partisan songs), which immediately positions the memorial, its content and message into the realm of popular culture and mass consumption. Importantly, for this writing as well, such interventions feature as triggers of Yugonostalgia, because they most explicitly refer to a particular period and radially address a past that has no present. It does have presence, precisely through such interventions and in the lives of people who were brought up to the sounds of Yugoslav popular music.

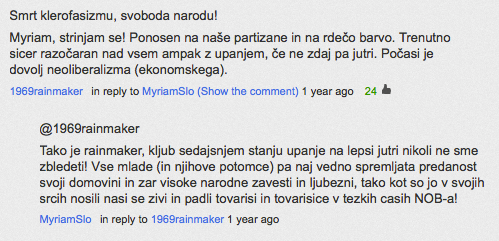

See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ge7KoJxSgSc&feature=related (Računajte na nas (Count on us))

The video uses a cover version of a popular song ‘Count on us’ written by Đorđe Balašević, a Yugoslavian/Serbian singer-songwriter and released in 1978. The cover was recorded in 1998 by a Slovenian band Zaklonišče prepeva and became a hit and a flagship song of Slovenian Yugonostalgic ‘movement.’[16] Visually, the user relies heavily on Che Guevera imagery, thus placing the narrative within a popular referential framework of international socialism. Photographs are interspersed with text (captions), which are transcripts of Guevara’s speeches, Fidel Castro’s admiration of Che and user’s own thoughts:

Translation: Ps. We’ll tear you apart like beasts. It won’t be difficult to do it again.

Visually and textually, the video is not a too great achievement. Regardless, since 2007 when it was first put up, it has been seen nearly 2 million times and has scored 8.372 comments (by October 2012), which says a lot about the place of this song in post-Yugoslav cultural memory and also about the emotions this cover version stirs in the post-Yugoslav debate about the past, present and future.

The comments section proves a ‘goldmine’ of affective responses (commenting activity can be detected throughout the video online period; at the time I watched it the most recent comment was 21 seconds old):

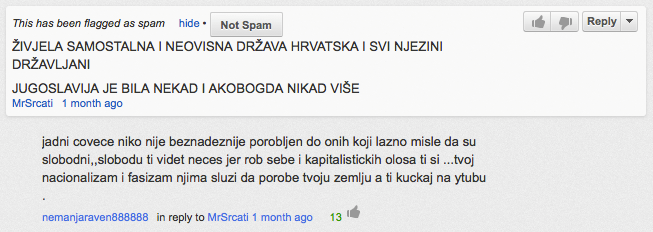

Translation: MRScrati LONG LIVE INDEPENDENT STATE OF CROATIA AND ALL ITS CITIZENS

YUGOSLAVIA WAS ONCE AND IF GOD SO WISHES, NEVER AGAIN

Nemanjaraven888888 in reply to MRScrati

you are pathetic, no one is more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe that they are free,,freedom you don’t want to see cause you’re the slave of yourself and capitalist basterds, you are …your nationalism and fascism serve them to enslave your country but you just go ahead type away on ytube .

Here a historical antagonism surfaces which was to an important extent part of the 1980s nationalisation and radicalisation of the situation in Yugoslavia. The socialist past, WWII and the resistance was exposed to a significant questioning. In the process of rising national sentiments, across Yugoslavia topics emerged related to rehabilitation of WWII collaboration. These topics remain present ever since and importantly shape national politics, most decidedly in Slovenia and Croatia. In this case we can see reference to the Independent State of Croatia, which was a Nazi sponsored state shortly before and during WWII, its officials responsible for some of the cruellest crimes in the territory of former Yugoslavia. The respondent exposes another issue present in dealing with Yugoslav past related to country’s historical position in the world; nemanjaraven888888 alludes to concepts of freedom, nationalism, capitalism, enslavement aiming to disclose the present situation as far from more free or democratic as was the Yugoslav. This is falls into the category of one of the more common tropes, i.e. that of conceptualising Yugoslavia as a country that at least on some level ensured greater freedom.

It can be argued that such vernacular memorials fail to translate their active potential into ‘real’ action. Often it all stops at posted video and commenting, while any further action cannot easily be traced and followed. This however, may not be an issue, as it is clear that such interventions do in fact arouse substantial response, if only digital. But the thing is that even such response has impact on users and viewers in terms of ‘presence.’ Number of views, comments, likes/dislikes all allude to the ‘impact’ of the video and even if these numbers are low, the very ‘presence’ of the content is not to be underrated.

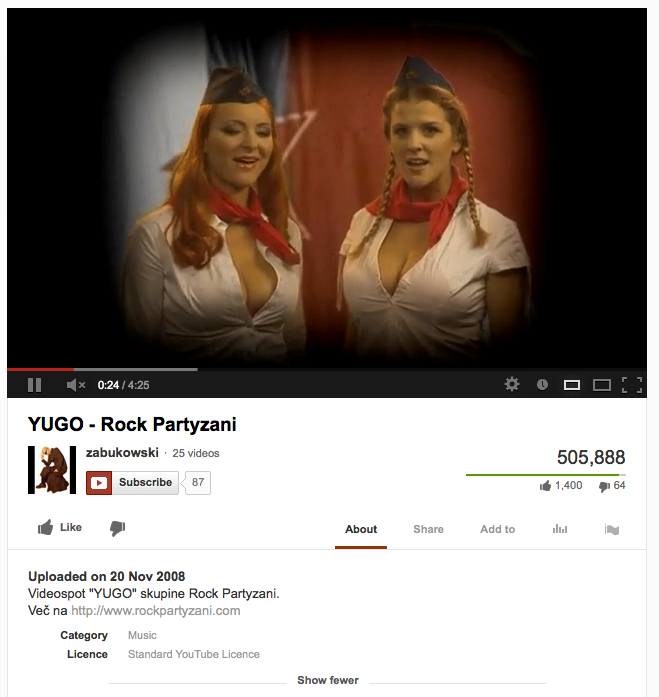

The case below reveals that the ‘provenance’ of the vernacular memorial video not necessarily plays any role in its reception. Be it a guerrilla statement or a commercial enterprise bears little or no consequence on the politics of emotion that develop in the comments section. The case of Rock Partyzani is a revealing one.

See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WQzqV-6-4do (Yugo – Rock Partyzani)

Here (this is the band’s official video) we can see explicit referencing and re-evaluating the Yugoslav, socialist past, including its political and popular aspects. The video features emblematic images from the period of Yugoslavia (Yugo, the Yugoslav car, mountains, commercials, excerpts from football matches etc.), which determines historical, popcultural and ideological limits of the video. The name of the band stresses this is a rock band while making reference also to the WWII partisan resistance. At the same time, the band introduces a word play, exchanging “i” for “y” this turning the partisans into entertainment. On the level of the band name they make reference to two important pop-cultural/historical phenomena: rock music, which in Yugoslavia played an important role particularly from late 1970s to end of 1980s, and the legacy of resistance. However, wrapping all this in entertainment they deliberately establish distance from these legacies. This is particularly relevant with a view to the fact that the main protagonist of this band was the key figure in another Slovenian pop-rock band Agropop, which in the late 1980s and early 1990s happily sailed the wave of nationalist emotions in the then de-Yugoslavising Slovenia. Thus it is difficult not to see a clear commercial aspect and commercial ‘exploitation’ of the sentiment and disappointment over the present-day situation through uncritical and not too inventive referencing the past.

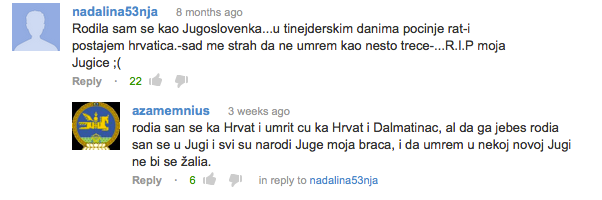

The responses to the song (it has over 500.000 views and over 700 comments), however, prove that when it comes to triggering emotions and evoking youth, such deliberations are useless:

Translation

nadalina53nja: I was born as a Yugosalv… when I was a teenager, the war began and I became a Croat.-now I’m afraid I’ll die something the third-…R.I.P my little Yugoslavia;(

azamemnius in reply to nadalina53nja

I was born a Croat and I’ll die a Croat and a Dalmatian, but fuck it, I was born in Yugoslavia and all nations of Yugoslavia are my brothers, and to die in some other Yugoslavia, I wouldn’t complain.

Apart from many cases that use music as the backbone of their narrative, there are several other cases that are not strictly YouTube content, but deserve special mention because of their treatment of the WWII topic.

See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gox2tEvwG-8&feature=related (Partisans, trailer)

This is a low budget production by an amateur production group Pristava Pictures. It involves just a few actors playing Partisans and Germans and is a ‘story’ about two bravehearts caught in the war in 1941. The trailer is meant as a parody of the period as it tries to portray humorously two partisans left with no ammunition and running helplessly through the woods. The Nazis are just as derogatorily portrayed as a disorganised bunch, marked by oversized swastikas on their helmets and the heavily Slavic accented German.

Another case, made by director Žiga Virc is a trailer for the film Battle at Vojsko.

In this case the author undertakes a more elaborate approach including more elaborate editing, mis-en-scene, costumes…

See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xVCu4TBg-hM&feature=related

(Bitka na Vojskem, trailer)

In this case considerably more attention is paid to the detail (weapons, trucks, uniforms, people). Now, the interesting part about this, apart from the comments that I will look at below, is the fact this trailer was made for a very specific event: re-enactment of an actual battle that took place in 1944 in Vojsko, Slovenia (see http://zbiralci.com/forum/viewtopic.php?t=7626) organised annually by the Culture-Historical Association Triglav. What is intriguing in this case is that the trailer actually supports a real (re)event, which is in all manners of its execution, a film. The trailer and the re-enactment taken together reveal a continual presence of interest in WWII that goes beyond merely ideological aspects, but is itself also very material; the uniforms and weapons used are all original.

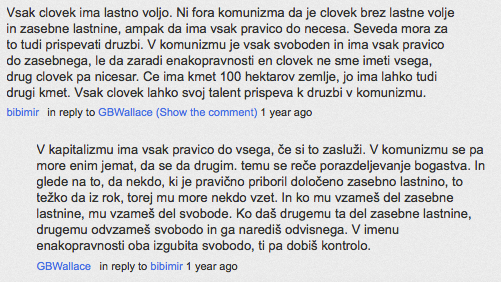

Translation:

bibimir: Everyone has his own will. It is not the point of communism that everyone is without his own will and private property, but that everyone has a right to something. Of course, everyone should also contribute to this society. In communism everyone is free and everyone has the right to property, but because of the principle of equality one cannot have everything, and another nothing. If a farmer owns 100 hectares of land, so can another farmer. Everyone person can contribute their talents to society under communism.

GBWallace in reply to bibimir: In capitalism, everyone has a right to everything, if one deserves it. In communism, one has to take from someone to give to the other. This is called the distribution of wealth. And given the fact that someone who has just won certain private property, it is difficult to just give it away, so it has to be taken. And when you take a part of private property, you take away a piece of freedom. When you put this piece of private property to someone else, you take away his freedom as well and make him dependent. Thus, in the name of the equality both lose freedom and you gain control.

This exchange reveals a basic controversy in contemporary post-socialist understanding of socialism as ideology and also alludes to the way socialist period is understood and perceived in post-socialist Slovenia. Conceptualising socialism as ideology most often spans uncritical adoration and just as uncritical condemnation, as a rule giving little room to its more nuanced interpretations that could fruitfully be used in understanding the present condition and conceptualising potentialities of the future. The voices of bibimir and GBWallace, both individual interventions into the digital media ecology, but due to media presence nevertheless relevant, significantly contribute to the conflation of complexity and inflation of simplification. As difficult as it is to embrace wholeheartedly the failed ideology of socialism, it is just as difficult to discard it entirely. Precisely in the time when crucial tenets of socialist ideology, as more or less successfully enacted in socialist Yugoslavia, e.g. solidarity, freedom, etc. are severely threatened by the present crisis and seeing everything through financial viability.

It is through this prism that much debate ignited through such and similar videos/vernacular digital memorials unravels online and is then further extrapolated to include contemporary cultural, political and economic situation in post-socialist Slovenia, and elsewhere. Juxtaposing the socialist present and the post-socialist, transitionalist present reveals a great deal of disappointment and unease both in understanding the past, as it does in making sense of the present. Thus such juxtapositions feature as indicators of present-day Slovenian culture-political divisions along the lines related to the interpretation of WWII and the role of socialism in Slovenian history.

Blogging as a practice and source of memory and remembering

As opposed to videos and memories and debates triggered through them, blogging is a more ‘traditional’ approach in the sense that it relies predominantly on the written word. Blogging is in a way the most straightforward continuation of dairies and commonplace books in terms of individuality of content presentation. Yet, it is also an activity that revels in the advantages of commenting and embedding audiovisuals.

In the case of ‘history on blogs’ I look at a selection of blog posts by authors who responded to the two events. Through their interventions I trace debates and hence collective interventions into public space.

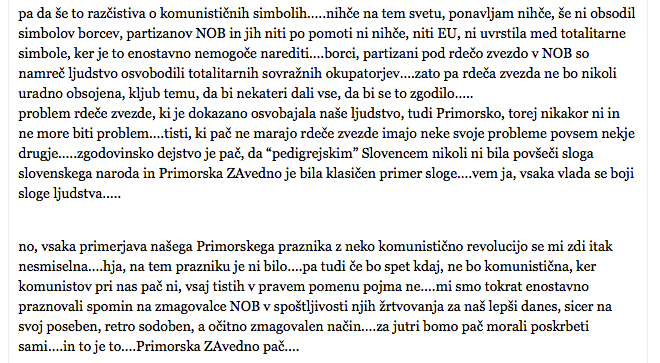

First I look at a blog by Don Marko M who posts regularly on various topics related to Slovenian daily politics and focus on his post related to the celebration of the restoration of Primorska to the motherland.

See: http://markom.watoc.org/2012/09/17/primorska-zavedno-z-rdeco-zvezdo-foto/ (all citations from this address)

Translation:

Primorska (FOR)eever – in the heart and with the red star (photo)

Camaraderie, strength and love, all in the name Memory eternity specified period of resistance and fighting our only real liberators, on Saturday okupiralo Koper. Over 70 thousand Primorska and those who like Primorsko we make sure that the Koper Cup at the seams in the most visited one day event for 25 years. We celebrated the 65th birthday Primorska. Memorable. As remains unforgettable thanks to our fighters, partisans, which can all celebrate. We are aware – without you, dear companions and comrades, there would be no us …..)

In his post from 17 September 2012, two days after the celebration of the Day of Restoration of the Primorska Region to the Motherland, Don Marko M gives a very engaged account about the event and its Slovenian historical and present-day political dimensions.

Translation: Celebration in Koper was also a beautiful display of generations of all ages comin together, from the youngest to the oldest, from the fighters, partisans and to banner carriers and their young, who cherish and will not forget their heroic acts. Apart from the central celebration virtually every inch of the city area was a sight of festivity.

At every step, the red star, children singing, fighters songs, camaraderie, love and rock’n’roll. All this is rock’n’roll and therefore we love it unfergettably. What the fighters, the partisans have begun, we continue.

Contextualisation of the event into the post-socialist and antifascist tradition is very overt and presents a crucial aspect of Don Marko M’s blogging engagement. Likewise, the urge to fight the revision of history and annihilation of the specific part of Slovenian past, one related to WWII and post-socialist period, is just as persisting:

Translation: So we spent an unforgettable day in camaraderie, love and harmony, that is completely normal day in Primorska, but this one had more memory charge. A bullet that will never be extinguished.

Companions and comrades, thank you! Thank you for your hearty fighting for this country and for the triumph, because of which today, even 65 years later, we live freely on our land. Thank you for your courage, for your heart, for the love of future generations – thanks for the Primorska. All this we will carefully cherish. We respect and preserve our Partisan past and march in victorious future. It is time for radical change. It is time for separation of Primorska from the motherland …

Death to fascism, freedom to the people!

Comrade Don Marko M

This rather lengthy post ends with the above wording, clearly replicating the socialist (liberation struggle) ideologised political rhetoric, which is ‘extended’ into the post-socialist period. It is this use of that specific rhetoric that in a way gives credit to the struggle. In fact, Don Marko M’s style of writing clearly shows great devotion not only to the legacies of socialism in relation to Primorska (liberation, restoration). In the same vein the author clearly builds on the ‘revolutionary rhetoric’ when talking about the future, which for him is unimaginable outside the continuity with the national liberations struggle tradition. Simultaneously, through the recognition of values equated with socialism (but not necessarily socialist in origin) the author re-fits the socialist past with historical meaning and relevance. What is more, doing so he effectively defies the historical cut of 1991 and the ensuing revisionism and establishes a continuity with socialist ‘heroic past.’ Thus he effectively re-endows the present with a sense of epochality.

Another point worth mentioning and that bears consequences also for the wider argument, is what the author explicates in the debate with one of the readers stating:

Translation (second paragraph): Anyway … I wasn’t in Koper [on the 15], but the stars and Tito’s image are logos of communism and nothing else, and this celebration was, judging by your pictures, most exceptionally highlighted. More so than at previous celebrations. And this is a provocation. And this is no coincidence. It has its own message, which was also probably understand.

and let’s get the communist symbols straight ….. no one in this world, I repeat no one, has condemned the symbols of the fighters, NOB [national liberation struggle] partisans not even by mistake, nobody, not even the EU, defines them as totalitarian symbols, because it is simply impossible to do so …. the fighters, partisans who fought under the red star in the NOB have in fact liberated people from the occupying totalitarian enemy …. so the red star will never be officially condemned, although some would give everything for that to happen …..

the problem of the red star, which has liberated our people, and Primorska region, therefore is and cannot be a problem …. those who do not like the red star have problems somewhere else completely….. but it is a historical fact that ‘pedigree’ Slovenians have never been too fond of the unity of the Slovenian nation … and Primorska Forever (Primorska ZAvedno) is a classic example of unity …. yeah I know, every government fears the people unity …..

Well, any comparison of our holiday with a communist revolution seems pointless anyway …. Well, at this event there was nothing as such…. and even if there will ever be again, it will not be communist, because there are no communists here, at least not those in the straight sense of the term…. this time we just celebrated the memory of the winners of the National Liberation Struggle in respect of their sacrifice for our better today, true in its unique, retro-modern, and obviously winning way …. we’ll just have to take care of tomorrow ourselves …. and that’s it… Primorska forever ….

The references the collocutors make in their debate to communism and the red star as its symbol are indicative of the post-socialist situation as they express a basic ‘dis-understanding’ about the strategies of ‘translating’ the ‘totalitarian’ past into a ‘democratic’ present. Robert Kaše explicitly links the red star with communism (predominantly its totalitarian aspects), which corresponds to generally detectable strategies in post-socialist countries (and Slovenia in particular) of wholesale discrediting of the socialist period through its equalisation with dictatorship, and comparing it to fascism and Nazism. Such understanding neglects or actively downplays the emancipatory potential (which in many socialist countries was realised to a significant extent) that the socialist project had and fascism and Nazism never did. With emancipatory potential I refer to investment in and development of public education, public health, emancipation of women (for instance, socialist Yugoslavia enforced universal suffrage in 1946, while for instance Switzerland in 1971), workers rights, etc.

Don Marko M on the other hand sees the red star not as a symbol of communism, but as a symbol of liberation, particularly of his native Primorska region. Explicitly differentiating the red star from communism (which in many respects is indeed difficult to do), Don Marko M in fact recognises the emancipatory potential of the liberation struggle and the period that followed, while acknowledging the problematic aspects of communism in general and also the specific situation in Yugoslavia and Slovenia.

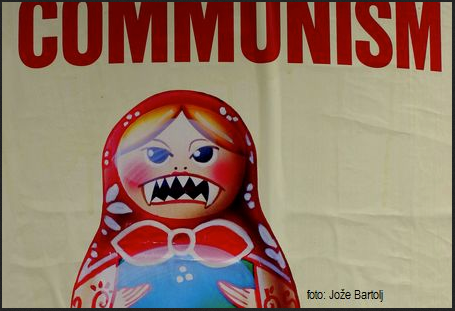

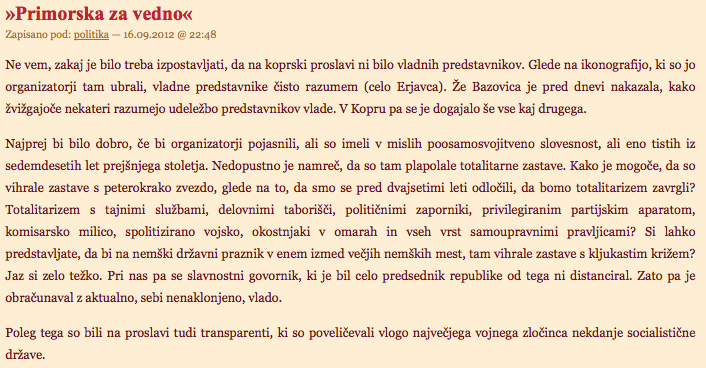

Unlike Don Marko M, who defends the emancipatory legacy of resistance and socialism, the author of Jože Bartolj – zapisi; Aktivno beležim (Jože Bartolj – Notes; Actively recording) blog takes a very different stance, condemning the period and ideology in question altogether.

See: http://jozeb.blog.siol.net/2012/09/16/%C2%BBprimorska-za-vedno%C2%AB/

This is clear from the very ending of his post related to the 15 September celebration, a photo of the Prague Museum of Communism advert:

Such simplified understanding of the complexities (also present at the Prague Museum) of the past swiftly deals away with any opposing views, tends to recognise no alternatives and see nothing else but ‘grey’ past.

Translation: I do not know why it had to be emphasised that no government representatives were present at the Koper celebration. According to the iconography, government officials can be understood (even Erjavec). […]

First, it would be good if the organisers explained whetehr they had in mind a post-independence ceremony, or one from the 1970s. It is unacceptable that totalitarian flags fluttered. How is it possible that flags with the five-pointed star were there, given that twenty years ago we decided to dispose of totalitarianism? Totalitarianism with its secret services, labour camps, political prisoners, privileged party apparatus, committee militia, politicised army, skeletons in the closet and all kinds of self-management fairy tales? Can you imagine a German national holiday in one of the major German cities, where flags with the swastika would flutter? I find it very difficult. And here the keynote speaker, the President of the Republic has not distanced himself from it. Therefore, he has confronted the current government.

In addition, at the celebrate banners fluttered hailing the role of the biggest war criminal of the former socialist country.

In his writing, the author perpetuates one of the most popular fallacies, i.e. that of conflating Nazism and socialism through the perspective of 1991. True, in 1991 Slovenia renounced its Yugoslav past (and future), the related symbols, ideology etc. as symbols of totalitarianism. However, the political operation that backboned the independence project failed to translate the complexities of both WWII and the post-war/socialist period into a meaningful, wholesome, national, culturally and politically sound narrative of the past. Instead, the independent political elites opted for a full-on obliteration of the socialist past, discarding with it also the above mentioned emancipatoryness, social, cultural and political achievements.

Interesting in this respect is the following: ‘Apart from this, present at the celebration were also banners glorifying the role of the greatest war criminal of the socialist state.’ What can be read from this statement semantically is that it suggests that people carrying banners saying (S Titom v srcu smo nerazdružljivi in nepremagljivi/With Tito in our hearts we are undividable and undefeatable) were glorifying the Josip Broz’s role in the post-war mass extra-judicial killings. Rather, what these banners suggest is that, as one commentator argues, it is not about unreflected defence of the system but ‘appreciating in it what was good.’

Translation:

@ jože, In Vipava valley, at least until recently, they had a similar inscription tito, such as the one on Sabotin. but it is true that these things are changing with new generations; young people more often than not do not care about these things, not to say anything about your case, where it’s mostly people who are definitely mostly the supporters of SDS [Slovenian Democratic Party; currently in power] and their propaganda. […]

I also do not understand why it is so hard to understand that the people in Tito and NOB and socialism appreciate what was good and not just everything. No one supports the war and post-war crimes, we support and celebrate what was good. And liberation from the occupier was certainly an honourable thing of which we can be proud. Unfortunately for you, we were liberated by the partisans and their symbols, so it’s not clear to me how do you imagine to celebrate something without the symbols that represent this.

Translation: Natasa: Antiklump, Ciril Zlobec said it best: “The other side of our history feels that it does not matter if there was no Primorska, as long as there would be no communism. And which historic achievement can they set for a public holiday? Oath to Hitler. No one in Europe celebrates this.”

Antiklump:

Ciril Zlobec in political terms is strongly “contaminated.” Too bad he did not remain a poet, because he was good.

Without communism Primorska would include Gorizia and Trieste. Violent worshipers of Stalin, worse than him, were impossible to stand up against, because they were ruthless. Unfortunately, their ruthlessness shows today. The system, which has historically flunked after some seventy years, and here alrady after after forty-five, a system built on lies, deceit and violence.

My dear, in such a way you will not solve your frustrations. Temporarily your consciousness is soothed, last this will not last.

Nataša: Then it would make sense to introduce a state celebration of the day the Homeguards swore oath to Hitler and name it day of resistance against the occupator? Antiklump, go easy on the transparent right-wing platitudes on frustrations…

The above exchange illustrates another common operation related to the concepts of Slovenianness, patriotism, national interest…, i.e. the post-1991 sanitisation of Slovenian past and present. In political and media discourses, predominantly those ‘nationally burdened,’ it is fairly common to adopt the discrediting strategies based on ‘marking’ a stance and/or the utterer as ‘ideologically contaminated.’ This effectively prevents any meaningful debate and in essence proves that the so-much-desired standards of free debate, expressing opposing opinions and argumentatively contesting opinions are wilfully discarded as soon as debate hits the delicate area of the national and the newly democratic. Sadly, rather than an argument about content we get an argument about allegiances, which invariantly leads to impasse in any potentially fruitful debate. Instead of official censorship we get self-imposed censorship which emanates from precisely such unproductive contamination of debate.

The content or a problem is thus rarely discussed despite the potentialities of the medium. Rather such posts become triggers for emotional re-working of the past-via-present: audiovisual and/or textual statements are labelled as contaminated if the utterer’s past/background is seen ‘inadequate,’ if the statement might too positively reinterpret, renarrate, remediate the Yugoslav past. Thus the past in terms of factual accuracy becomes temporally conflated and radically simplified. On the other hand, such individual interventions might also be seen precisely (or firstly) as ‘provocations,’ as triggers that set off individual memories and (socio-politico-cultural) engagement. A reaction to a post is usually emotively laden, it is radically motivated by personal relation to the topic, to the period in question.

Conclusion

As stated in the beginning, this is not a definitive or all-encompassing overview of the historical representations in DME related to Slovenian history. In fact, the scope is deliberately limited to the post-socialist condition and only a selection of cases. This was a decision based on the importance of understanding the socialist experience in Slovenian context; and understanding the importance of understanding the role of socialism in as a significant part of Slovenian past and history, and also present-day discourses.

To better illustrate this I took as a starting point two pivotal events that marked the Slovenian political scene in 2012 and resonated quite loudly in digital media ecology as well. Purposely I did not look at newspapers but rather at bottom-up interventions. Not only because of scarcity of material I also took in consideration some material which is not explicitly connected to the two events, but that still remediate the topics which were renarrated in vernacular treatments of these events: the WWII (resistance, anti-fascism, collaboration) and the post-socialist period.

This of course does not mean that other historical topics are not present in Slovenian DME. Rather the dominance of WWII and post-socialist period is incredible. Understandably, this is to be attributed to the nature of Yugoslavia’s demise, to the formation of new states and to the global trends in conceptualising and managing liberal-democratic/capitalist states and affairs. The multimodal discourse analysis of the selected content (media objects) through the perspective of the two cases shows that the past in Slovenia is far from commonly shared, and is interpreted in a radically bi-polar manner. It is clear that on an astonishingly small territory that Slovenia is two very strong narratives coexist about what in a democratic state the meaning and role of WWII and its ensuing interpretations should be. It is astonishing that in very specific interpretations (speaking in European terms) of the WWII, anti-fascist resistance and the post-socialist period, the relevance of the socialist past and its role in the former Yugoslav’s histories is very easily discarded in its entirety.

Of course, uneasy questions arise as to how to accommodate a regime that is responsible for mass killings after the WWII with the obvious emancipatory effects that the introduction of socialism had for the Yugoslav countries. Discarding the entire socialist period is not particularly productive in attempts to define a long-term view of a country’s development. Neither is it a particularly promising point of departure for conceptualising national history in the wider, European historical framework.

Sadly and worryingly, this seems to be the problem that underlies and defines the East-West relations in the EU today. The ‘former’ West seems very reluctant to renounce its victorious role (the German guilt for the WWII and the Holocaust being ‘resolved’ in Nuremberg), whereas the East is heavily traumatised by the legacies of Nazi occupation and to an important extent also Soviet occupation on the one hand, while on the other also by the present-day unacceptability of its socialist/communist past. Thus, in line with what Buden states (quoted above), regardless of internal differences (e.g. Yugoslav experience is radically different from Estonian) the East is in the position where they cannot rely on their 20th century as a source material for creating possible futures. Effectively, the East, and particularly the former Yugoslavs (Slovenians, Croats, Bosnians, Serbs, Montenegrins and Macedonians) are left without any longlasting meaningful or heroic past. And the online interventions as described above are in many respects also an attempt to reassemble the historical and reattribute the past with a sense of normalcy, epochality and heroicity.

Predominantly because of mediatisation and mediation of the quotidian (and with it memories and remembering), which has so distinctly marked the latter 20th century, it is the mediated past (popularisation of the historical and historicisation of popular) that defines the audiovisions of the past most decidedly. And it is upon this excessive mediatisation of the past that the ideas of the future can be built. The East, however, in the process of de-sovietisation, de-totalitarianisation, de-Yugoslavisation, de-communistisation, etc. is left without ‘useful’ content that could legitimately be used in constructing the pasts and the futures. Caught in ‘permanent transition’ not only is the socialist past ‘useless’ for official, state-sponsored historiographies and but it is largely inappropriate for any kind of positive (re)evaluation. It can be, and it often is, selectively used for post-socialist, nationalistic self-purification, i.e. ‘self-decompetentisation.’ Thus the present becomes very difficult to trans-code into a ‘myth,’ into a narrative that would have stood the chance to succeed in constructing a post-socialist political, social or cultural tissue. This effectively means that the west retained the east as its ‘other,’ (or rather that the East retained its role as the West’s other), only now it is no longer the ‘communist’ but the ‘infantile’ other.

Thus a way is needed indeed, and many of the analysed cases do exactly this, to reinterpret the ‘inappropriate’ socialist past into a meaningful past (this does not imply neglect of its negative chapters). Only then can former Easternites find their place in a common Europe and only then can a common Europe hope to arrive at a commonly accepted approximation of an idea of a common future.

Bibliography

Buden, Boris. Zona prelaska, O kraju postkomunizma. Fabrika knjiga, Beograd, 2012, 39, 42.

Hoskins, Andrew. ‘The Digital Distribution of Memory.’ Available at www.inter-disciplinary.net/wp-content/…/hoskins-paper.pdf, accessed 21 December 2012.

Krippendorf, Klaus. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 2004.

Lundby, Knut (ed.). Digital Storytelling, Mediatised Stories: Self-representation in New Media. New York, Peter Lang, 2008.

Manovich, Lev. Software takes command. Draft book, 2008. http://lab.softwarestudies.com/2008/11/softbook.html. Accessed 8 August 2011.

O’Halloran, Kay L. ‘Multimodal Discourse Analysis.’ In K. Hyland and B. Paltridge (eds.), Companion to Discourse. London and New York, Continuum (in press 2011).

Parikka, Jussi. What is Media Archaeology. London, Polity Press, 2012.

Pogačar, Martin. Memonautica: Yugoslavia in Digital Memories, Memorials and Storytelling. University of Nova Gorica, 2012 (PhD Dissertation).

Sobchack, Vivian. ‘Afterword: Media Archaeology and Re-Presencing the Past.’ In Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka (eds.), Media Archaeology, Approaches, Applications and Implications. Berkeley, Los Angeles London, California University Press, 2011.

Velikonja, Mitja. Titostalgia: A Study of Nostalgia for Josip Broz. Ljubljana, Mirovni inštitut, 2009.

Note:

[1] Lev Manovich, Software takes command. Draft book, 2008. http://lab.softwarestudies.com/2008/11/softbook.html. Accessed 8 August 2011.

[2] With this term I denote the type of networked activity which involves an individual, a networked machine and the internet. Hovering attention implies distributed, fragmented attention dedicated to stuff going on online and is related to a filtering out ‘interesting’ content in the general inability to follow ‘everything.’

[3] On re-presencing see Vivian Sobchack, ‘Afterword: Media Archaeology and Re-Presencing the Past,’ in Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka (eds.), Media Archaeology, Approaches, Applications and Implications, Berkeley, Los Angeles London, California University Press, 2011, 323-334; see also Martin Pogačar, Memonautica: Yugoslavia in Digital Memories, Memorials and Storytelling, University of Nova Gorica, 2012 (PhD Dissertation).

[4] On multimodal discourse analysis see Kay L. O’Halloran, ‘Multimodal Discourse Analysis,’ in K. Hyland and B. Paltridge (eds.), Companion to Discourse, London and New York, Continuum, in press 2011.

[5] See Jussi Parikka, What is Media Archaology, London, Polity Press, 2012.

[6] I use terms ‘East,’ ‘Eastern’ and ‘Easternite’ as symbolically laden terms and am aware of their essentialising capacity. I do, however, wish to emphasise the still existing division and also allude to ‘self-easternisiation’ of the former socialist regimes.

[7] Boris Buden, Zona prelaska, O kraju postkomunizma, Fabrika knjiga, Beograd, 2012, 39, 42.

[8] Ibid., 61.

[9] Ibid., 61.

[10] Knut Lundby (ed.) Digital Storytelling, Mediatised Stories: Self-representation in New Media, New York, Peter Lang, 2008.

[11] Manovich, Software takes command.

[12] On the on-the-fly see Andrew Hoskins, ‘The Digital Distribution of Memory,’ available at www.inter-disciplinary.net/wp-content/…/hoskins-paper.pdf, accessed 21 December 2012.

[13] O’Halloran, ‘Multimodal Discourse Analysis.’

[14] Klaus Krippendorf, Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 2004, xiii.

[15] See Pogačar, Memonautica.

[16] On Yugonostalgia see Mitja Velikonja, Titostalgia: A Study of Nostalgia for Josip Broz, Ljubljana, Mirovni inštitut, 2009,